REWRITING THE MISSING PAGES OF HISTORY, ACCESSING NEW REPRESENTATIONS

Oral tradition, as opposed to historical documents, is paramount here because culture, as in ‘the intelligence of past men’, is passed on not in ashes but as living fire.

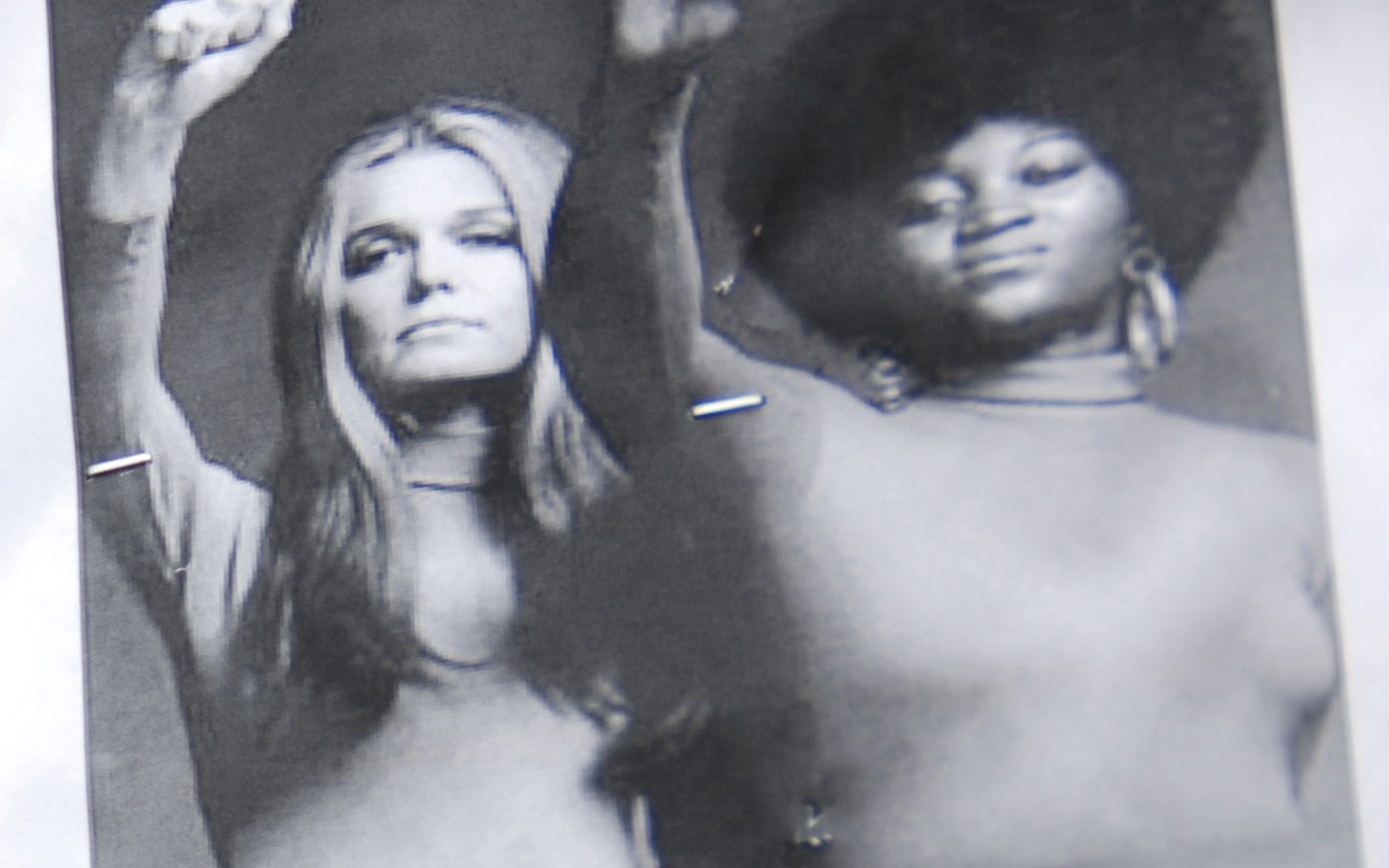

In On the Concept of History, Walter Benjamin warned us: ‘History is written by the victors’. This is why feminists speak of ‘His-tory’. Indeed, ‘…historical scholarship, up to the most recent past, has seen women as marginal to the making of civilisation and as unessential to those pursuits defined as having historical significance’.Gerda Lerner, founder of Women’s history, with her course on ‘Great Women in American History” in 1963. Eco-feminist art faces this challenge. Relying as it does on the missing pages of women history, it is not rooted in His-tory, but upon Heritage, as the lasting ethos of the occulted and suppressed history of half of humanity.

Not only women, natives and animals’ history was never recorded, but Leonard ShlainShlain, Leonard, The Alphabet Versus The Goddess. The Conflict Between Word And Image, 1998, Viking Press. proposes that the written language, in its linearity from left to right, literally before and after – at least in the western world – presents constraints that are antithetical to the very formulations and expression of some ideas and notions, like principles of simultaneity, multiplicity and immanence, that are central to eco-feminist art. Shlain makes connections across a wide range of subjects including brain function, anthropology, history, and religion, and argues that literacy reinforced the brain’s linear, abstract, predominantly masculine, left hemisphere at the expense of the holistic, iconic feminine right one. Shlain points out that the first book to be written, the Old Testament, banned any visual representation of god, suppressing long standing artistic traditions of devotion to the goddess, and believes that the increasing use of images and icons as means of communication, play fundamental roles in human consciousness, with inevitable repercussions on gender identity and relations’.

‘The Medium is the Message’. Ursula K. Le Guin’s also maintains that the way we tell stories has feminist implications for understanding history and for imagining the future. In ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, Le Guin proposes that storytelling has not always been about a hunt with a beginning, middle, and end, but can be a meandering sweep—a gathering.

Indeed eco-feminist art plays an important role, because not only it tells what history cannot, but because identifying totems, symbolisms and creeds adopted by male and female artists often working in oppressive regimes, reveals and reawaken a conception of Nature that pushes beyond the physical realm and extends into a wider super-natural dimension – a sacred living energy of the cosmos.

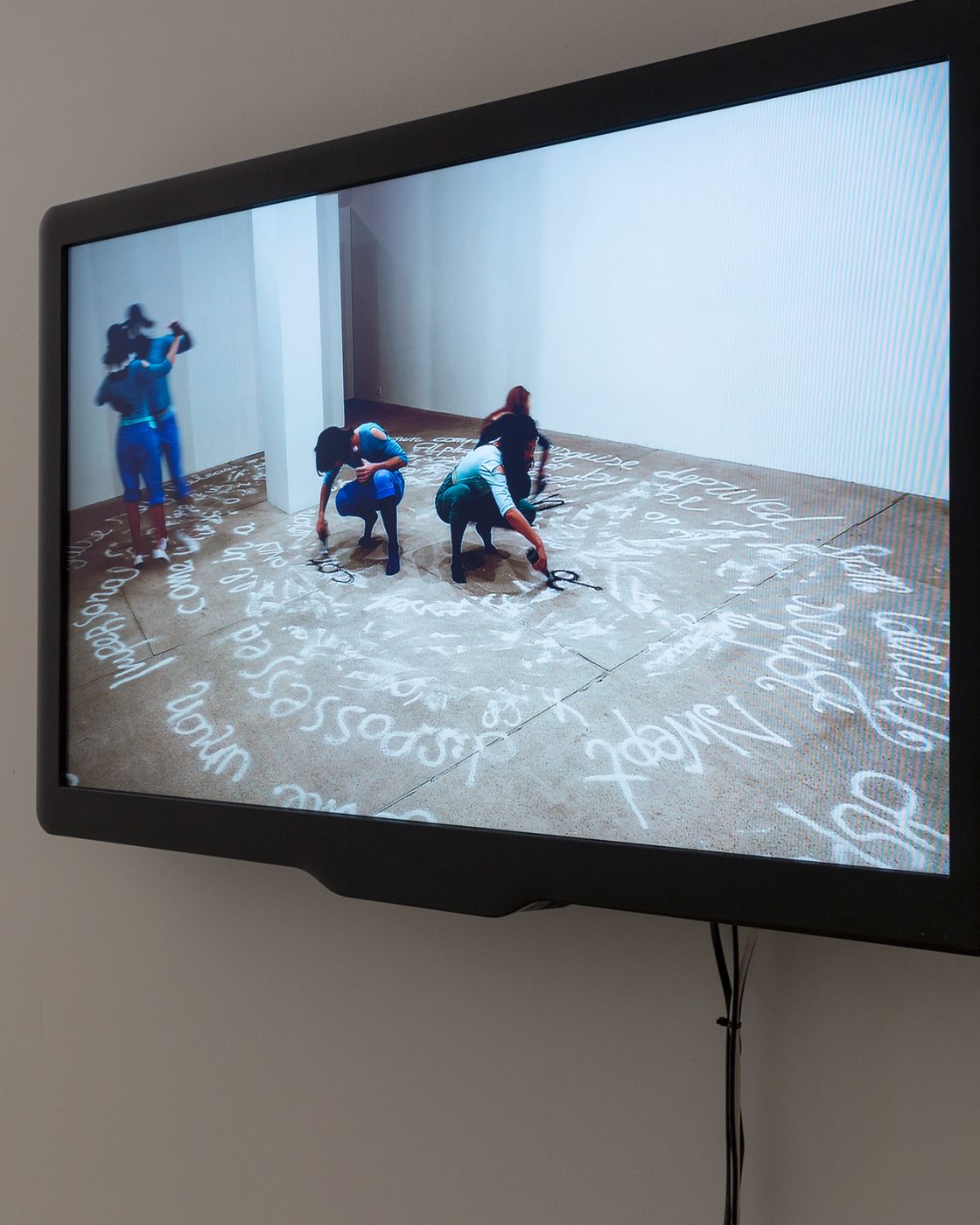

By resurrecting ancient belief systems which have been bleached out of history, and adopting and activating speculative worlds, contemporary artists are questioning systems of knowledge, biology, ecology, geology and anthropology, moving beyond the supremacy of the visual and the constraints of language, and immersing the viewer (or feeler?) into a ‘liminal space’.

This space is away from the biases and prejudices in which human utterance is soaked and allows sensation to disrupt and expand human consciousness. Progress in this sense, is understood not as in the increase of knowledge, but in freeing it from its wrappings.

Feminist art’s emphasis on the body, is therefore crucial. As St. Hildegard of Bingen wrote a thousand years ago, ‘we understand so little of what is around us, because we do not use what is within us’. Donna Haraway also appeals for the introduction of a feminist epistemology, providing the ground upon which contemporary artists are formulating a newly ‘inclusive aesthetic’Bourriaud Nicolas, Inclusioni, L’Estetica del Capitalocene, Postmedia Books, 2020. aimed at disrupting the canon.

Since Feminist artists resurrected the figure of the goddess as an archetype for feminine consciousness and a model for re-sacralising women’s bodies and the mystery of human sexuality, far from the simple idolisation of women, the figure of the goddess became a symbol of life, connection and responsibility. In large part thanks to the pagan Wicca movement, the Ggoddess became a catalyst for an emerging earth-centred spirituality, and a metaphor for the earth as a living organism. Eco-feminist theorist Carolyn Merchant powerfully demonstrates how the interchangeable view of women and nature will inform and allow the scientific revolution’s project for the subjugation and exploitation of both, providing the ground for contemporary capitalism. Merchant highlights the misogynist language adopted by Francis Bacon, one of the founders of Modern Science: ‘I have come in very truth leading you to nature with all her children to bind her to your service and make her your slave’ and the implication of Rene Descartes’s view of human bodies.Merchant Carolyn, The Death of Nature. Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution, Harper & Row, 1980. Susan Bardo describes the process of detachment from an organic world, as a ‘drama of parturition, a flight away from the feminine, far from the memory of union with the maternal world and a rejection of all the values associated with it’Bordo, Susan. The Flight to Objectivity: Essays on Cartesianism and Culture. Albany: State Univ. of New York Press, 1987., which is replaced by an obsession with distance and demarcation. ‘The machine to make the new man was also a machine to kill old women’.