Stream: Over ten years after the creation of ArchiLab,1 and after having taken a five-year break, what is your analysis of the different avenues of architectural experimentation and the various urban issues as they have been identified by the millennial generation? Have any turning points or breakthroughs occurred since 2008?

Marie-Ange Brayer: Since the first ArchiLab event was held in Orleans in 1999 by Frédéric Migayrou and me, the fact that digital technology has led to an epistemic shift in the field of architecture has become a given. Yet, at that time, the atmosphere in France was resistant to such a “digital revolution.” Fourteen years after the first event, this ninth edition of ArchiLab introduces a new generation of architects for whom digital media have formed an integral part of their approach. In the first editions of the event, it was still difficult to realize complex projects like those of Karl Chu or Ben van Berkel (UN Studio). ArchiLab 1999 nonetheless saw Greg Lynn articulate his generative grammar (the Maison Embryologique) by way of wooden molds, plastic casts, and rubber imprints, which made his theory of “blobs” official for the first time. Inspired by D’Arcy Thompson, they were organisms that evolved in response to their environment.

Computational artifact

The 2013 edition of ArchiLab strikes today’s reader with the expressive force and the formal complexity of the projects it presents, highlighting the emergence of a new, multi-scalar computational artifact that can be brought to fruition at any scale, from the design object to the city. That is what has changed in today’s world: architects can now simultaneously work at many different scales, from the local to the global, using the design software at their disposal. Computerized Numerical Control (CNC) machines directed by 3-D printers were used to produce almost the entire exhibition of this event—from the young stylist Iris van Herpen’s dress to the pavilions by Achim Menges. In 1998, the FRAC Centre public contemporary art collection had already shown the very first architectural objects by Objectile (Bernard Cache and Patrick Beaucé), calculated on computers and produced on CNC machines. Each individual object was unique and yet able to be produced industrially. “The new status of the object no longer refers its condition to a spatial mold—in other words, to a relation of form-matter—but to a temporal modulation that implies as much the beginnings of a continuous variation of matter as a continuous development of form,” wrote Gilles Deleuze in The Fold, on the subject of Objectile’s research. The emergence of formal variability has transformed the status of the object, which henceforth inserts itself into multiple temporal layers.

Stream: It seems that the mobility of new technological tools, together with the notion that each user of urban space evolves along with his or her own microsystem, has accentuated the transformation of our relationship with space (augmented by the virtual), and time (accelerated, multiple, and fragmented). Has this phenomenon had any particular influence on architectural practice over the past ten years?

Marie-Ange Brayer: The precursory Architectures Non-Standard exhibition at the Centre Pompidou that Frédéric Migayrou organised in 2003 was a topical milestone. 3-D printers will soon be a part of our everyday lives and non-standard architecture, which is both unique and industrial, will be a reality in the near future. Our daily activities are already deeply enmeshed with the use of individual and mobile technology. In a reference to Guy Debord in the ArchiLab exhibition The Naked City that he curated in 2004, Bart Lootsma also took on the subject of technological mobility in the discipline of architecture. Moving from situationism and the dérive to the flash mob and individual tools for spatialization and communication, he addressed the issue of the interconnection of local and global tools as they have affected architectural practice. Today, architects such as Theodore Spyropoulos (Minimaforms) rethink modes of communication. Their projects emphasize cybernetically-informed behaviour, “proto-architectural environments,” and participatory models. What is surprising in architectural practice today is that we have gone beyond the idea of a spatial or geometric framework in order to explore complex and evolving forms of temporal dimensionality. The electronic artifacts in the 2013 edition of ArchiLab, Naturaliser l’Architecture (Naturalizing Architecture), are all morphogenetic—their formal qualities could have manifested themselves differently. They have taken on a genetic approach to form and a cognitive comprehension of space-time. The designer Joris Laarman’s Bone Chair, for example, allows us to see the movement of bone growth. Material space is heightened by the virtual, which is also the nature of the work on the organic printer by Ruy Klein in New York—it is capable of “printing out” elements from the living world.

Digital material

Stream: The importance of energy and environmental issues, like the role of information and communication technologies, is well established. Do you sense a sort of understanding that may allow society to engage with experimental architecture and its speculative research?

Marie-Ange Brayer: ICTs are inextricably linked to the research that architects perform. In 2011, at the FRAC Centre, when Gramazio & Kohler with Raffaello d’Andrea presented the first architectural module that was not built by human hands but by flying robots, they were advocating the simultaneous timeframe on which both design and execution could take place. Moreover, when Achim Menges made HygroSkin Meteorosensitive Pavilion (FRAC Centre collection), he revisited the hydroscopic properties of the material (wood), all the while employing advanced technological research that allowed him to embed micro-particles into the pores that both opened and closed according to the perceived level of humidity. The search for energy efficiency utilizes new technologies that disappear from the superstructure as such and find themselves incorporated into the materials themselves, giving way to a low-tech and high-performance form of architecture that is responsive to its environment. That is where the revolution is, in the integration of technology into the materials—yet another example of which is the self-assembly by Skylar Tibbits

Stream: What is clear here is the importance of the transdisciplinary dimension in these types of research: new forms of knowledge, tools, and collaborations that assume a new attitude, a change of position, and a way of being for these architects. How, in your opinion, has the perception of the discipline evolved for this generation of architects?

Marie-Ange Brayer: The transdisciplinary aspect is inherent to all the processes that share the same digital substrate; the same base. Architects, artists, designers, and scientists alike use identical simulation software, with its corresponding programming languages. These practices are porous; new configurations surface between architectural and scientific convention. Today, for example, you can use Processing, the programming language designed in 2000 by the artist Casey Reas and Ben Fry, much as the catalog designers for ArchiLab did in order to actively rethink the typography. All of the tools are available and that inevitably opens the doors for research and multiplies the number of interactions. A new form of “digital materiality” is common to every field. Designers and architects point to the emergence of a new form of “digital craftsmanship..

Naturalisation et hybridation

Stream: Naturalizing Architecture explored the issue of the simulation of the living world and aiming towards a “metabolic” form of architecture capable of developing along with its environment. Can you explain this concept of “naturalization”? In moving from simple morphological mimicry to a bona fide generative simulation, would the goal be to create a super-natural form, a sort of hybrid between nature and technology?

Marie-Ange Brayer: The naturalization of architecture is about addressing nature in a different way, no longer as an opposition between the natural and man-made, but in a new sort of hybrid relationship. Architecture is imagined here as an “enhanced artifact,” as Neri Oxman puts it (ajouter une réf à l’entretien avec Oxman? see p. XX). At once organic and mechanic, this new artifact has infiltrated the fields of research and creation. Here, architecture brings together the biological and the computational, leading to a fusion of what Minimaforms calls “natural and synthetic systems.” These creators claim to have stopped designing architectural objects, instead producing “a process that generates objects” (Michael Hansmeyer). Naturalization as we speak of it is an evolving form of materiality that functions as much on the local as the global scale. Through the use of modeling software, architecture aligns itself with living systems—systems equipped with a “metamorphic” nature and distinguished by their transformability and adaptability in response to their environment.

From the organicist approach of Goethe, who studied the dynamic morphology of plants with Ernst Haeckel, the origin of living species is attributed to the interrelation of individual organisms. Haeckel’s 1909 study of radiolarians, like the work of Robert Le Ricolais in the 1930s, took into consideration the “architectural” nature of microorganisms that present complex polyhedral geometries. When the biologist Aristid Lindenmayer put forth his models of the growth patterns of plants in 1968, it influenced the language of computer programming. Buckminster Fuller pointed out the structural analogies between radiolarians and his geodesic domes. Then later in the 1970s, René Thom highlighted the link between math and nature through the process of morphogenesis (Stabilité Structurelle et Morphogenèse, 1972), and Ilya Prigogine advocated the self-organization of matter and the disruption of “dissipative structures,” whose propos was not unlike that of the physicist Stephen Wolfram (inventor of the software Mathematica in 1988), who ceaselessly explored the relationship between computing and nature.

Stream: Who are, in your opinion, the major players in the contemporary field of architectural research when it comes to the border between nature and technology? What are the major concepts which bring them together? How do they differ from past examples of biomimetics which have regularly emerged in the history of architecture?

Marie-Ange Brayer: Today, decades after the invention of the computer and well after the onset of the electronic age, the field of architecture has devoted itself to a dynamic partnership with the disciplines of biological and life science, neuroscience, synthetic and molecular biology, thermodynamics, physics, chemistry, artificial intelligence, and cognitive science. Architects also scrutinize these systematic approaches to life, examining the possibilities of its replication, and its ability to self-organize and re-emerge, all of which encounter, at present, the nature itself of digital technology; the “computational ecosystem”. The protagonists who work on nature-technology research are everywhere. They can be found in universities and laboratories around the globe. In this particular issue of ArchiLab, we can cite Neri Oxman from the MIT Media Lab; Achim Menges at the technical university of Stuttgart, who works on the pairing of engineering and architecture; and Gramazio & Kohler at the ETH Zurich, in robotics.

For Manuel De Landa, self-organizational processes have blurred the boundaries between the organic and non-organic worlds. Architecture has made it a priority to be a hybrid and composite organism, in interaction with its environment, informed by its materials; an intelligent, high-performance system. The materials themselves have become producers of information. The task at hand is no longer one of imitating nature, reproducing its external forms as was the case with biomorphism, but to simulate it through a generative approach; to artificially recreate that by tapping into the self-organizational dimension of living systems. “Recourse must be made to the generative dimension, in which the tool(s) will therein be able to go beyond space and time,”² suggests Frédéric Migayrou. Biomimetics have not disappeared—quite the contrary—it has even been reaffirmed by Menges, and SOMA. Indeed, it is true that the history of architecture is very closely linked to our interpretation of nature. The Renaissance resulted in the first mathematizations of nature; mannerism left us with monsters and hybrid beings whose representations still dwell in the artificial caves and curiosity cabinets of the time. The norm has given way to heterogeneity. In this edition of ArchiLab, nature is no longer an “immanent plan” but has set itself to be the material condition for even the computational systems that can, today, further generate “synthetic living objects.”

Stream: Academic research, at MIT in particular, currently utilizes the notion of the living as a metaphor, but also as a framework for the analysis and general representation of the city. Above and beyond the scale of the buildings presented in ArchiLab, do you see a continuation of such concepts of naturalization at the global scale?

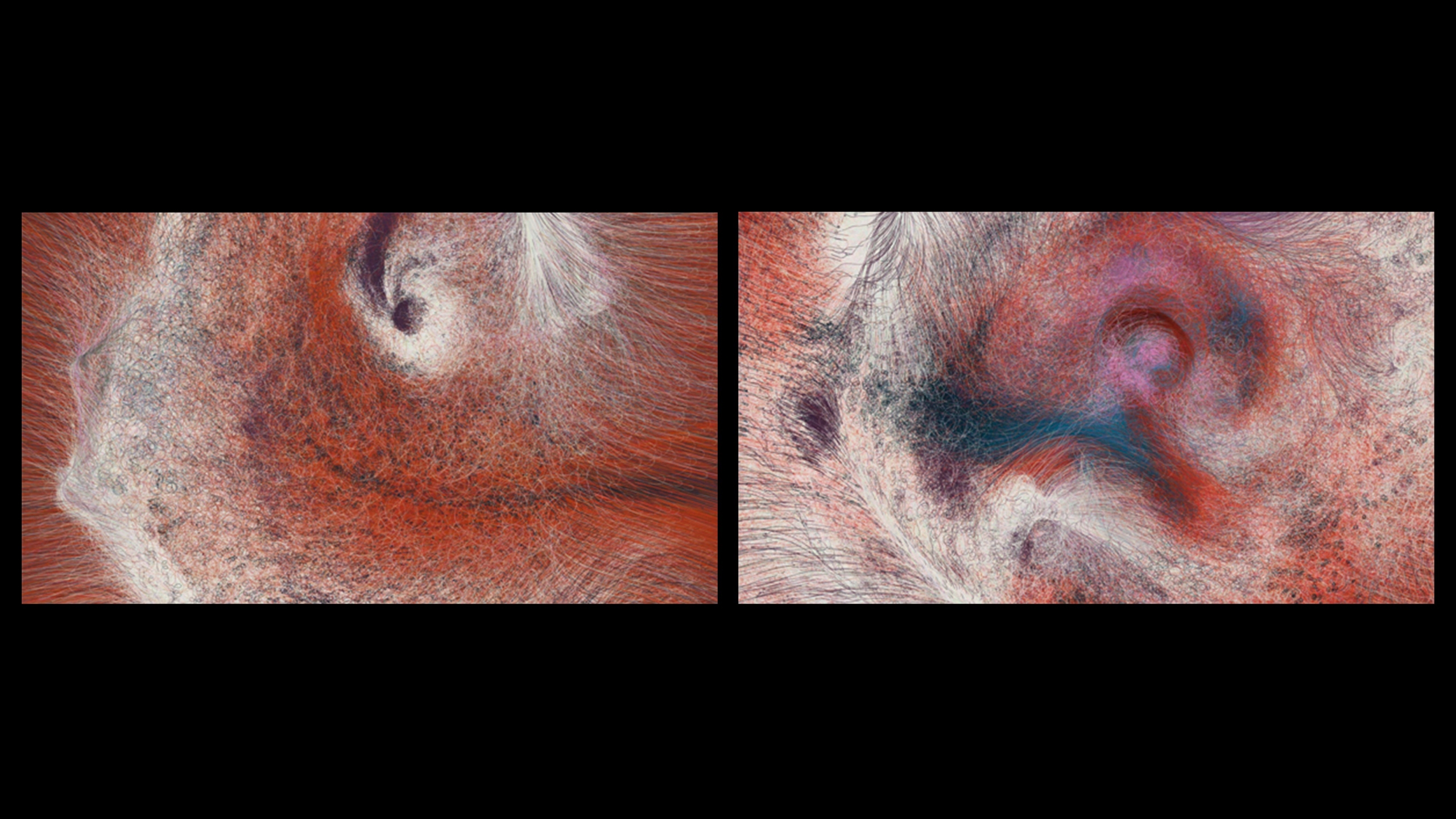

Marie-Ange Brayer: Both the idea of the naturalization of the city and the contextual dimension are present everywhere: thanks to the simulation software, Cellular Automata, Alisa Andrasek (Biothing) modeled the interaction of actors which complexified in “swarms”, combining architecture with the urban surroundings (ajouter une réf à l’entretien avec Andrasek? see p. XX). SPAN (Matias del Campo and Sandra Manninger) reflects upon urban development using as a starting point the recursive geometry of fractals, in an effort to consider models of the organic behavior of urban growth. The micro scale is inextricably linked to the macro scale, everywhere: from the individual design object to the global scale. This approach can be based on materials, such as the biotechnology research of X-TU (Anouk Legendre and Nicolas Desmazières), in which the use of microalgae allows them to reconceive urbanism as a biomass in constant evolution. Grotto, by Michael Hansmeyer (together with Benjamin Dillenburger), was produced by 3-D printers, and foretells a new sort of material complexity that could soon free itself from the limited scale of the printer in order to generate an evolving form of architecture at the urban scale. In Michael Hansmeyer’s work, the autonomy of the ornament has dissolved all tectonics and the geometrical comprehension of space in order to open itself up to a new cognitive space-time; malleable and—maybe even—reversible.

(This article was published in Stream 03 in 2014.)