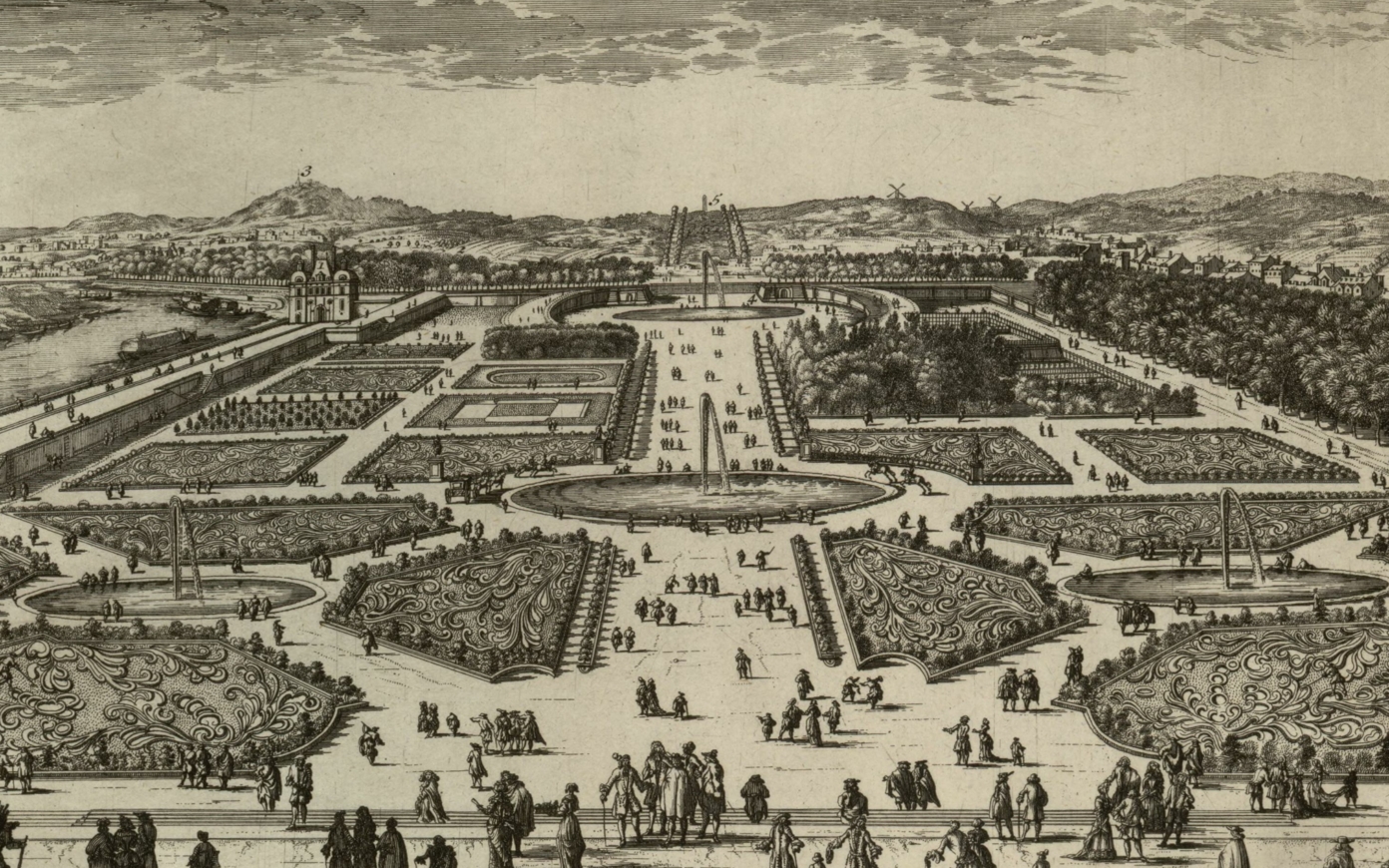

Professor in history of gardens and landscaping, Chiara Santini, recounts the significant history of the Champs-Élysées. They form an ambiguous space since their beginning: neither park nor boulevard, neither an urban landscape nor a rural one. Depicted as a domesticated nature by Le Nôtre, the Champs-Élysées mark the birth of a vision of the city as being open towards the countryside, seen as one of the models of Haussmann’s grandes percées. In the 18th century, the Champs became the recreational hub of Paris, thus an area of freedom for an aristocratic and bourgeois but also popular Parisian public (ou for the aristocratic and bourgeois classes, but also for the working one). It is because the Champs-Élysées was one of the first public promenades to be arranged in a « natural » environment, that Adolphe Alphand ended up choosing the Champs-Élysées gardens as testing grounds in the mid-19th century. The engineer invented a new form of garden, at the intersection between the classical garden and the picturesque garden: one of the prototypes of what was to be called the « modern garden », by featuring an irregular layout embedded in the axial grid of classical gardens. During the Second Empire, the Champs-Élysées turned into a reference for town planning, but was also transformed into a space for strolling and social representation and the staging of France’s horticultural knowledge and know-how, especially during the World Exhibitions. Chiara Santini invites us to consider the history of this unique palimpsest as « living »: a heritage to be protected with its quality as a dynamic, living space, opening it to the 21st century.