Living Beings

- Publish On 23 May 2024

- LVAO

- 7 minutes

La Vie à l’œuvre (Life in the Making), a collective of researchers in the natural sciences, humanities and social sciences, as well as artists, was set up at the Université Paris Sciences & Lettres in 2014 to explore interdisciplinary collective intelligence around the theme of the living. Functioning as an incubator of ideas, they explore the potential of living beings, particularly via experiments between art and science.

A Stream 05 – New Intelligences article to discover!

An interdisciplinary collective

The “Life in the Making” collective is an atypical group that includes researchers in natural sciences and scholars in humanities and social sciences, as well as artists. The collective was formed in the cross-disciplinary incubator called ‘Domestication and the Making of the Living’ created between 2014 and 2016 at the Paris Sciences et Lettres University as part of the CNRS’s Mission for Interdisciplinarity. Headed chemist Ludovic Jullien (ENS-SU), and anthropologist Perig Pitro (CNRS-Collège de France), the innovative program operated as an incubator for ideas and organized dozens of symposia and study days, followed by publicationsRefer to the web sites of the ‘Life in the Making’ collective (https://lifeinthemaking.net/en/) and incubator (https://domesticationetfabricationduvivant.wordpress.com) for more details. in order to collectively consider the problems raised by the definition of life.

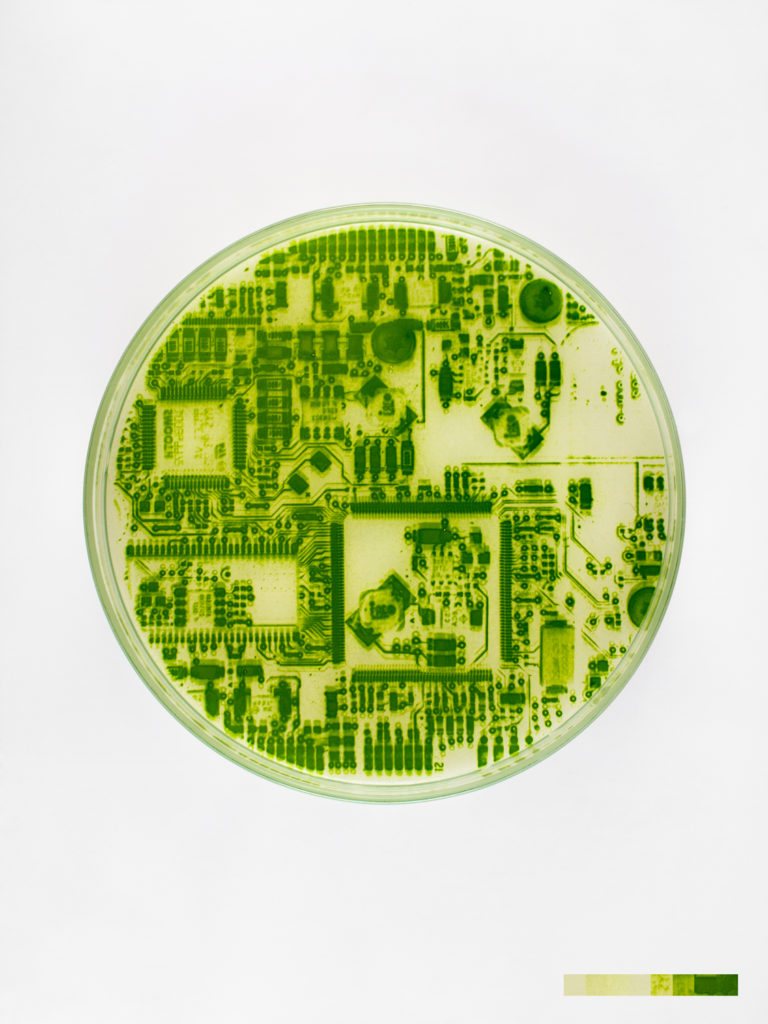

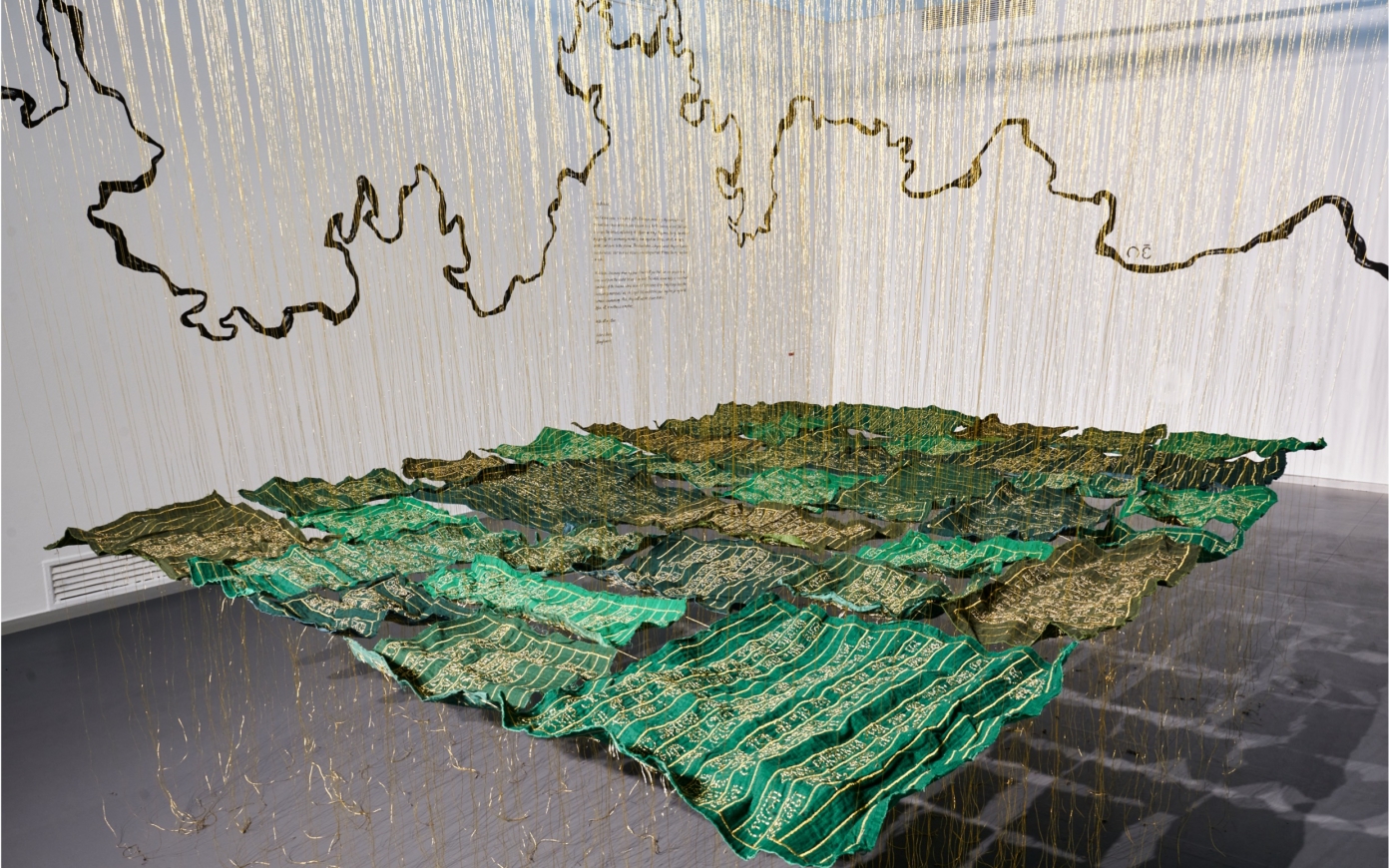

The momentum continued at Paris Sciences et Lettres between 2017 and 2019 with the ‘Life in the Making. Exploring the Potentialities of Bioart and Biodesign’ (La vie à l’œuvre. Explorer les potentialités du bioart et du biodesign) project, which developed experimentations between art and science with artists Lia Giraud and Dominique PeyssonThe project was spearheaded by Labex TransferS, in partnership with Labex Memo Life (IBENS), DEEP (Institut Curie), Institut Pierre-Gilles de Gennes (http://www.transfers.ens.fr/la-vie-a-l-oeuvreexplorer-les-potentialites-du-bioart-et-du-biodesign).. Within this very university, the ‘Origins and Conditions for the Emergence of Life’ program, deployed by the Paris Observatory, has provided further opportunities for exchange between natural sciences, social science and the humanities, and artists since 2017Since 2017, one of the ‘Strategic and Interdisciplinary Research Initiatives’ (Initiative de recherches interdisciplinaires et stratégiques) of Université PSL focuses on the topic of the ‘Origins and Conditions for the Emergence of Life’ (Origines et conditions d’apparition de la vie) at the Paris Observatory (http://www.univ-psl-ocav.fr).. In all these projects, the involvement of the ‘Anthropology of Life’ team headed by Perig Pitrou within the Social Anthropology Lab at the Collège de France fostered interdisciplinary dialogue, in particular through a new generation of students working on projects at the nexus between natural sciences and social sciences and the humanitiesThe ‘Anthropology of Life’ team (Anthropologie de la vie) investigates the diversity of biotechnologies developed by human societies on our planet (http://las.ehess.fr/index.php?2408).

These programs focused on specific priority topics, to ensure that the conditions for quality research are met while sharing a flexible approach to organizational activities. We had a great deal of freedom to determine the most suitable modalities of collaboration—including testing formulas that didn’t work out—and eventually our collective was able to develop an interdisciplinary collective intelligence practice, while establishing new knowledge about life and interactions with living beings. The institutional environment provided the conditions for researchers from several institutions to meet, however, it was in collaborating together that gradually brought about the formation of a relatively autonomous collective motivated by a shared interest in understanding the complexity of the contemporary world. Even though we did not continue receiving the funding that sparked the movement, in 2021, we created a nonprofit called ‘Life in the Making’ in order to project ourselves into the future and to deepen our discussions on living outside of academic spheres.

STUDYING LIFE: FROM PHENOMENON TO FOUNDING PRINCIPLE

The collective focuses entirely on the phenomenon of life. This is a subject area that has been examined for a long time. It might seem as though the probing would be drawing to a close, yet this is far from being the case. We have learned a lot.However, there is still much to be discovered about life—regarding its origin,its uniqueness, and its banality, as well as its definition and how the living evolve. We explore how technique, and human technology in particular, impact its trajectories. There is a vast subject matter, and we view its exploration as essential to the educated choice of the organization and the functioning of our society, as transplants and genetic engineering now make it possible to modify living beings well beyond breeding or education. To clarify our approach, it seems relevant to us to highlight the analogies between the way in which life produces different levels of organization and the way in which we have progressively developed a collective intelligence—as if a coalescence had gradually brought about, in us and with us, the emergence of a living being composed of a multiplicity of experiences.

Life has provided our collective with its evolutionary principle. For example, when considering new members, we subject them to individual assessments to evaluate what they can bring to the group. Mutual listening and discussion skills are paramount. In its initial condition, our collective involved a small number of people in a predefined institutional environment. It has, since then, transformed and started carrying out various projects, following more or less random encounters within a vast network of relationships, paying no heed to experience. Young students, for example, can rub shoulders with established figures. Though our collective has an organizational principle and the desire to undertake concrete actions, it has no predefined horizon. We like this metaphor of ‘evolutionary tinkering’ and the emergence of an everbecoming and highly indeterminate living organism with diverse components, rich in redundancies and in flexible and changeable internal interconnections. In practice, the life of the collective is punctuated by monthly meetings and retreats—alternating between having informal discussions and identifying objectives to improve their focus—visits to laboratories and exhibitions. The collective is involved in various joint projects, texts, exhibition scenarios, and artworks.

The living intricates many levels of integration. It cannot be resolved into the infinitely large or the infinitely small. It appears as an infinitely complex reality that can only be questioned through the collaboration and confrontation of many disciplines. This is in no way specific to the living world, however, and is, in fact, common to many topics requiring a systemic perspective, including health, climate, food, and so on. The way knowledge-producing institutions are organized follows a twofold logic—a legitimate one that recognizes the worth of disciplines through the value and the uniqueness of their point of view, and another, more questionable one, focused on managing a territory (including positions, financial resources, etc.). Confrontation with complex subjects that cannot be resolved by applying the knowledge of a single discipline is undeniably a drive force behind interdisciplinarity, which also addresses the hyperspecialization of individuals. A logical consequence of the advancement of science and technology, hyperspecialization generally leads to more efficiency, but also generates isolation, as well as a limited knowledge of the diversity of ways that can be used to explore reality.

ART AS A MEDIUM FOR A SENSITIVE EXPLORATION OF REALITY

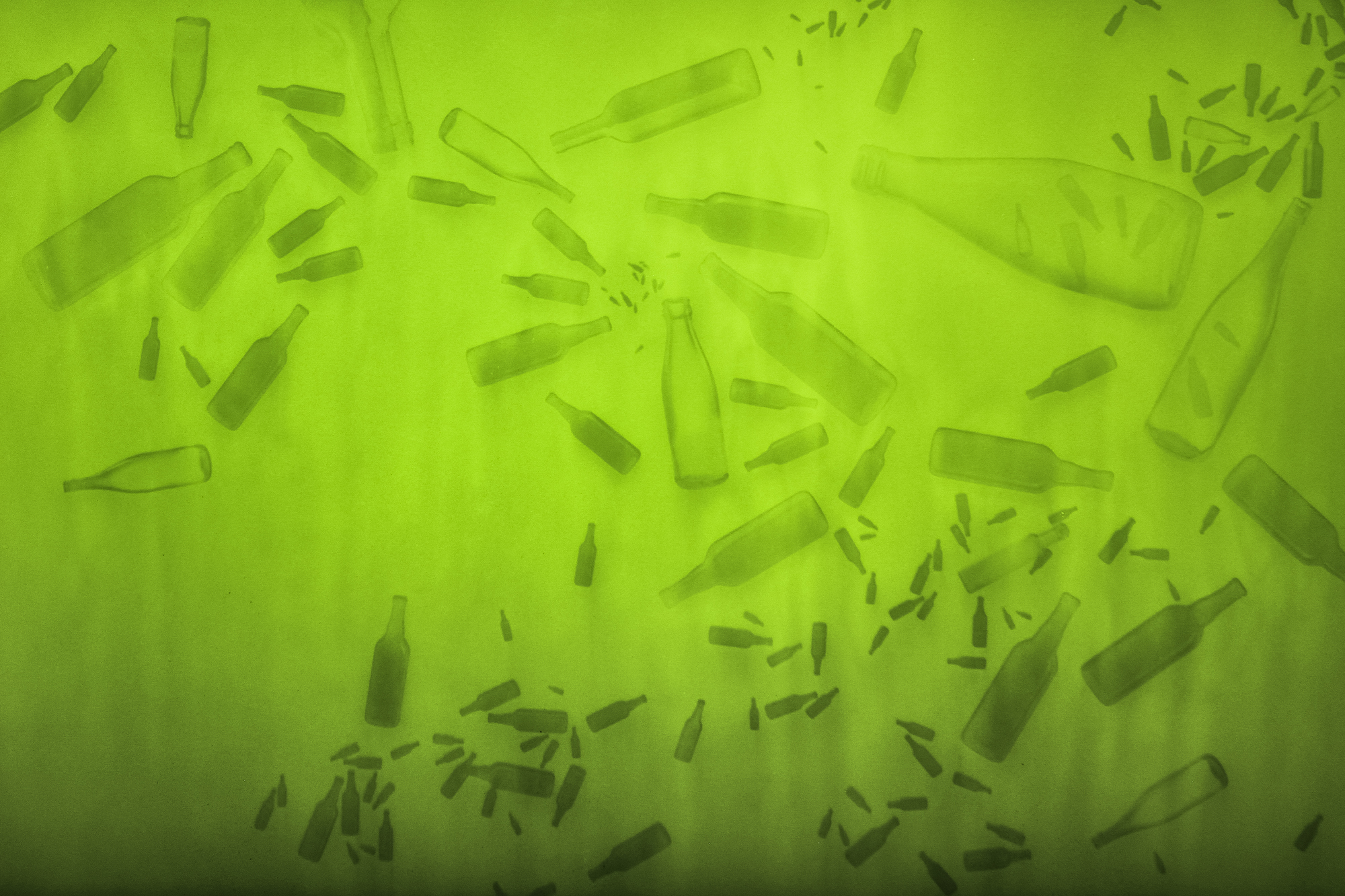

The idea of involving artists—and specifically bio artists—in the workings and reflections of the collective, came very naturally, in particular due to a convergence of action, as scientists and artists mobilize their imaginations to investigate the various possibilities of reality. Artists approach the relationship to the world in a specific way, however, starting from their feelings. They are therefore giving access to a different form of knowledge than that provided by the sciences. It is less universal, more subjective, but, for this reason, also makes it possible to include the sensible and affects in the relationship with scientific knowledge. They also reveal what we’d risk not seeing without them. Including artists in the process, therefore, reflects converging interests. Just like all other members of our collective, contemporary artists seek to position themselves in relation to our technoscientific society, even if they share their thoughts through the production of sensible objects rather than erudite communications, which makes them more apt to engage in dialogue with the general public.

The interaction between science and art results in obvious benefits given that artists manage to share ‘unintelligible complexities’ in ways that are less universal but just as important as those used by scientists. Their sensitive objects are of particular interest to the academic members of our collective, who consider them as relevant mediators to make visible—and therefore intelligible—what isn’t easily discerned in their activity due to their very nature or to the normative framework of community codes. As for artists, who engage in exploring fictions and representing possibilities, they can experience a broadening of their imaginations going well beyond mere physiological perceptions when exchanging ideas with scientists.