Could we imagine escaping from a utilitarian vision of nature, responsible for the crisis that we are undergoing? For example, the notion of ecosystem services is now widely used, although some people consider it to be a “commodification of nature”.

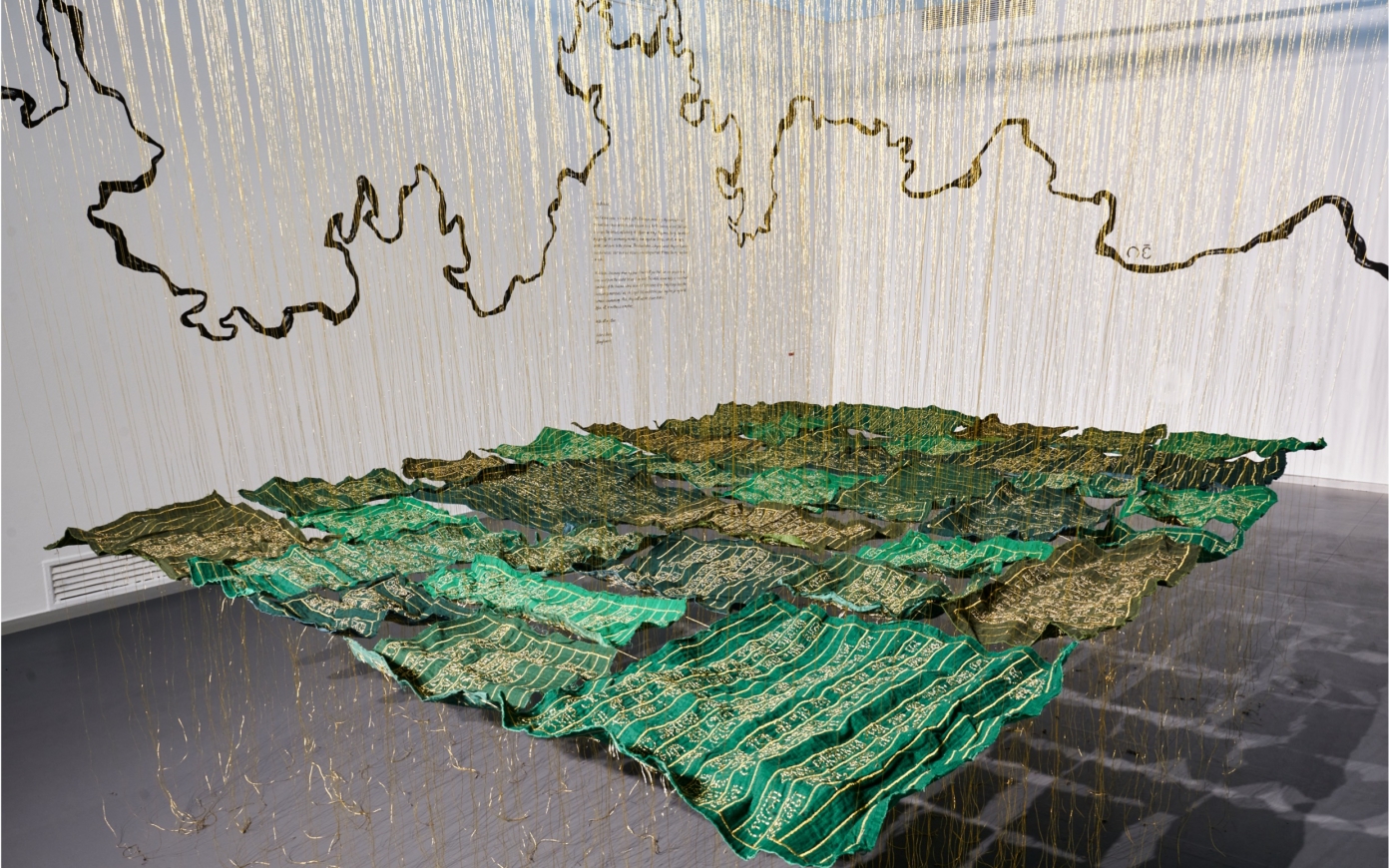

Ecosystem services collect together all of the benefits that human beings and societies derive from the functioning of ecosystems. Following the report by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, we can identify three major categories: supply services, i.e. all of the planet’s renewable resources like agricultural, forestry, and fishing resources, etc. ; regulatory services, a conceptual novelty, that concerns the functions of ecosystems that we benefit if from without being aware of it, through the recycling of carbon, water, nutrients, but also predation, pollination and cool zones; finally cultural services, the immaterial benefits of nature that we enjoy, like recreational, scientific and educational services, attachment to place, cultural identification, and even spiritual and moral values. I do think that this third category can absolutely not be described as a service, nor can it be reduced to the notion of benefit. It is a cultural or relational value that directly impacts human beings, their identities, their interests and their well-being in a much more constructive fashion than simple benefits.

If we only consider the first two categories, we can criticize the notion of ecosystem services for employing a kind of lexical mimicry of the world of economics. This term actually emerges from a desire to adopt the language of “deciders”, with a desire to make protecting nature a part of political agendas, that the ecologists of the last decade of the 20th century assumed were heavily influenced by economic agendas. The risk of commodifying nature does not actually come from this approach in itself, but rather from the economical evaluation of ecosystem services. These evaluations can be quite telling, and even useful from an “educational” point of view, I am thinking in particular of the famous study Changes in the global value of ecosystem services Costanza et al. 1997; Costanza et al. 2014, that in 1997 revealed that the totality of ecosystem services that nature provides us for free represents three times the global GDP measured in dollars; this continues to raise certain questions but a number of works refuse to invoke them.

To illustrate the problems that this poses, take the example of the city of New York. In the beginning of the 1980s, the city conducted an evaluation of the economic value of conserving the drainage basin of the Hudson in the Catskill Mountains. It was shown that maintaining these mountains in good ecological and hydrological condition was much more profitable than investing in water treatment plants to maintain a high quality of water. But the same evaluation redone in 2008, in the context of a financial crisis, with a drop in the cost of labor and technological tools, showed on the contrary that it had become more profitable to build water treatment plants rather than investing in the preservation of ecosystems… These methodologies of cost assessment can then stimulate public debate and participate in decision making, but they should not be the only element on which to base decisions, as they are debatable thanks to their temporal instability and dependence on context. These tools can be mobilized in certain specific cases, but they cannot condense the complexity of nature.

On a more fundamental level, the question of economic efficiency, part of an ideology of growth, appears to me to be at odds with the construction of a less toxic, less violent and less extractivist relationship with nature.

This involves thinking that the value of all things is solely economic. Is it not underestimating the deep value of nature?

Looking at nature uniquely through the prism of ecosystem services is the same as evaluating the value of a sentimental relationship based on a cost-benefit analysis: rent divided in half, sessions with a psychiatrist avoided, telephone fees generated…This calculation indicates the costs and benefits of a relationship, but in no way represents the true value of what it means to us. What is more, adopting such an approach risks adding a filter of accounting to one’s perception of a relationship, diminishing a partner’s ability to commit to it. Similarly, ecosystem services generate a flagrant under-evaluation of the profound value of nature by basing their approach on circumstantial data, which is of little value when it comes to considering its worth. The commodification that you’re talking about exists more on a symbolic level, one that implies considering nature as nothing more than a simple resource. For me the principal risk lies in our reduced capacity to be moved and to appreciate things for their intrinsic value. Like the example of the sentimental relationship, it is possible that the deep, authentic and disinterested values that connect us to the natural world will gradually fade to the point of disappearing.

Neither dualism, nor ecosystem services reveal a constitutive approach of the human being. They are complex constructions and systems that drag us both individually and collectively into a deadly relationship with the living. Not being a misanthrope, I don’t believe that other human beings are genetically programmed to be terrible torturers, dominators and predators; the issue today is then to revive our capacity for wonder, for interaction and for concern, in the sense of care, rather than holding back or letting these things peter out. This plays out on a philosophical and also political level, on the scale of the city, in the way we open cities up to nature and how we think about travel. It is up to each of us to rehabilitate this capacity that lies within us to care for others, and this includes non-humans.