Humankind against nature

In your book, the use of art as an interpretive lens enables you to dispel, or at least to qualify, the mainstream understanding of humankind’s anthropocentric relationship with the world since the Renaissance. What was the starting point of this research?

The starting point goes back to Pierre Huyghe’s exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in 2013, which was recommended to me by my friend Judicaël Lavrador. In an interview, HuygheSee his interview with Philippe Chiambaretta and Éric Troncy in Stream 03: Inhabiting the Anthropocene (Paris: PCA Editions, 2013) declared that his readings of Bruno Latour and Quentin Meillassoux—who endeavors to imagine a “world without humans”—didn’t only interest him but also confirmed his intuitions. I was particularly intrigued by this and, almost at the same time, rereading the part of Baudelaire’s Salon de 1859 where he talks about “the universe without man” and “nature without man,” ten years after my Ph.D. dissertation, something was triggered in my mind. I then decided to trace the genealogy of this idea or, more accurately, of the representations that artists form of it.

You identify three “moments” or “tragedies” that would historically explain the emergence of the great modern movements. How are these disruptions expressed in artistic terms?

In 1755, an earthquake devastated Lisbon and claimed several tens of thousands of victims over the course of two days. There were two conflicting interpretations of this horrible event: on one side, the conventional providentialist reading of the event, held by the Church, speaks of divine retribution which is beneficial to men; on the other side, a rational and enlightened vision, held by Voltaire and Kant for instance, laments a tragedy that stems from a contingency and states that nature isn’t moved by God’s spirit to punish men, but rather is an impersonal force that is indifferent to their fate. During the rest of the eighteenth century, a great number of major disasters occurred, giving rise to an eschatology that could be described as materialistic—in Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, in The Last Man by Mary Shelley, or in the writings of Saint-Simon among other examples. There looms a modern terror: that of an end to the human species that would arise independently from the end of space itself. Gone is the coincidence of the passing of mankind and the dissipation of history: the man could be gone and yet, history would carry on. What I make clear in the first part of my book is that, at the same time as this “anthropocritic” vision, there is also a promotion of annex spheres—animals, plants, and even “things,” if we consider for example the Barbizon school, Rosa Bonheur, Victor Hugo, or Jules Michelet—that also participates in the leveling of humankind’s place in the living world.

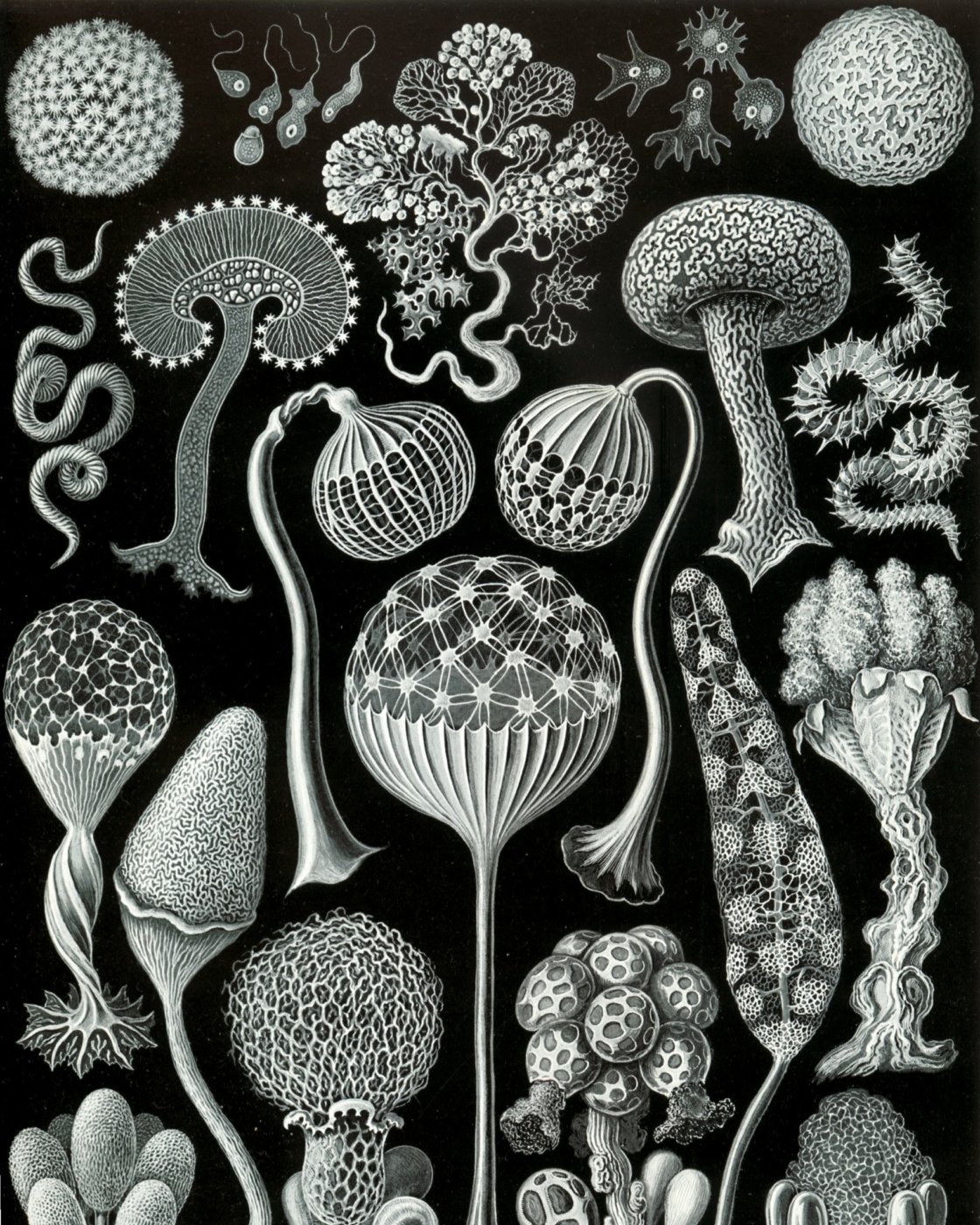

In 1860, then appeared the mental shortcut that designates man as descended from the ape, following the eminently outrageous success of Darwin’s Origin of Species. The narcissistic wound regarding the origins of man conclusively demolishes the fixed and unshakable representation of humankind, thereby reduced to an inconstant and temporary instance. I think we must consider the aesthetics of hybridization and the biological, physical, and mechanical speculations of symbolism or futurism as amplifications—either concerned or exalted—that are permeated with this new paradigm.

In August 1945 comes another moment of shock. Einstein himself declared that atomic weaponry “threaten[s] the continued existence of mankind.” Artists will produce many visual, literary, cinematic expressions of this potential eradication, and often very disturbing ones—I am thinking in particular of On the Beach, Nevil Shute’s excellent 1959 novel. The fragility of humankind becomes not only a motif but I would also say an artistic cause. And the problem isn’t nature’s random violence against man anymore but the chain of uncertain consequences stemming from the telluric action of humankind against nature, which is now the one that suffers. Hence a fascinating and stimulating paradox for the artists of the contemporary art scene: “The chasm of the Anthropocene, where anthropocentrism, which had just reached its full vigor, peaks precisely at that cut-off point after which the Apocalypse takes place.”