The ideal of the Situationists was urban situations, “constructions of a different kind, which should lead toward radically new forms of life”.Thomas Y. Levin, “Der Urbanismus der Situationisten,” arch+ 139/140, Berlin: 1998, p. 70.

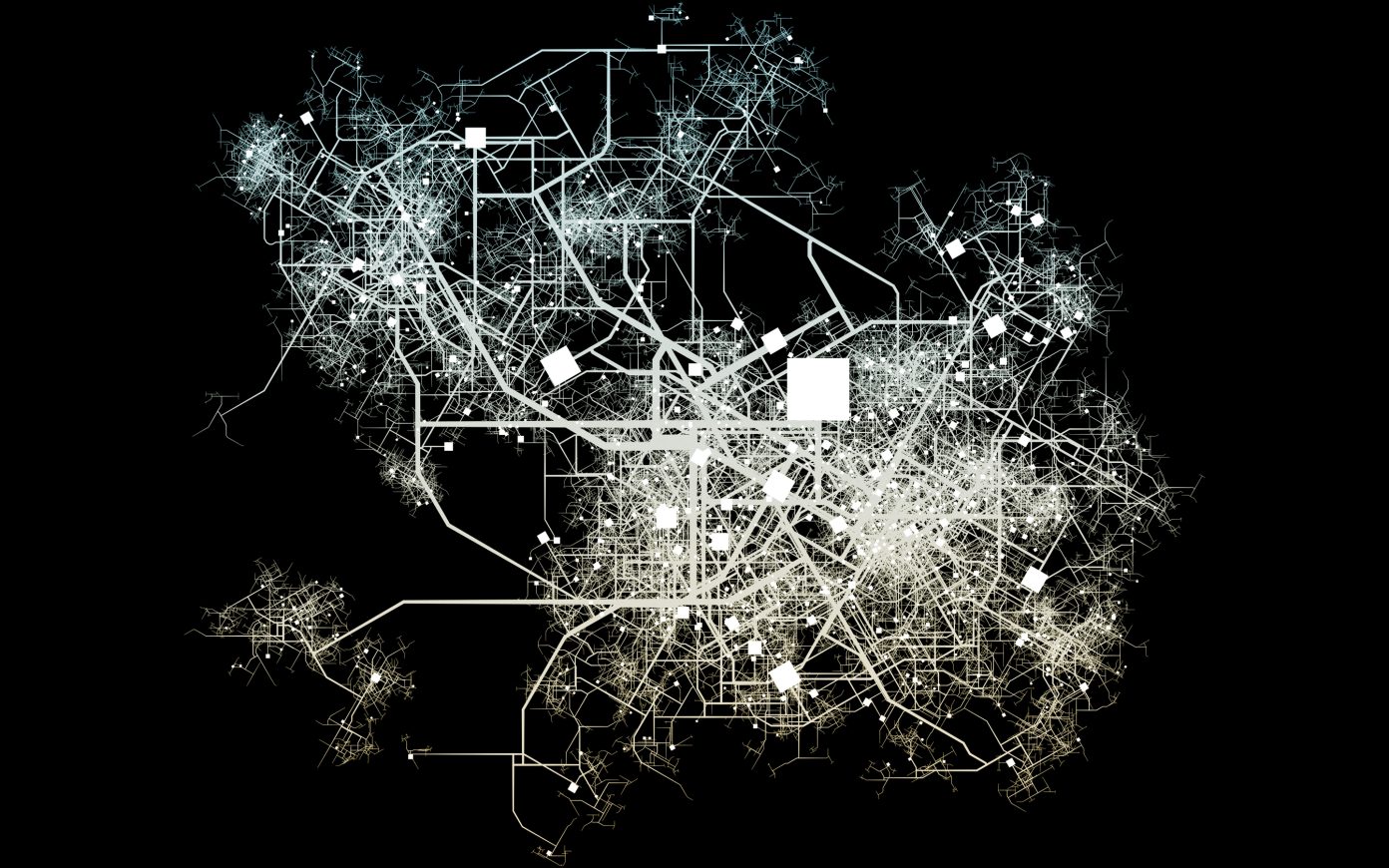

This city is characterized by the emergence of fortuitous events, movements, continuous change. “One day, we will build cities for wandering.”Debord, “Théorie des Dérivés’, cited in ibid, p. 75. The city of the future, as imagined by the Situationists, is a city of experiences, of dis-covery, of rebellions against the compulsions of a regimented life. “Every street, every animated square, could be the entrance to a metropolis, a prelude to a discovery through which life opens up, through which new faces are perceptible, with habits shed and familial duties or regulated professional lives now regarded as marginal epiphenomena, by which a free movement no longer cares to be disturbed.”Ivan Chtcheglov (Gilles Ivan), ‘Formular für einen neuen Urbanismus’, in I.S. NR 1, cited in Ohrt, Roberto, Phantom Avantgarde, Hamburg: 1990, p. 50. The architect of this city is no longer the designer of individual buildings, he is the creator of processes and atmospheres that allow room for the unfolding of individual freedom.

The fantastic city in place of the functionalist city

The analysis of the real-existing city as a functionalist, inhumane space, and the dream of a free city as counterproject: Here are the intersections between historical Situationism and Nike’s urban, experiential brand spaces. The imaginary Niketown, as the scenarization or simulation of a better reality, responds with exactitude to the drawbacks of the contemporary city as analysed by the Situationists: The absence of the magical, the unknown, the unforeseeable.

The urban brand spaces, then, emerge within voids of meaning torn open by the functionalism of contemporary urbanism, which subdivides the city in functional terms while seeking to extirpate everything wicked, abysmal, dark. The fan-tastic city, the dreaming city, the different city, that of desire and of secrets, has vanished, sanitized in the process of modernization, and divided into residence, living, working. Today, we are confronted by an emotionless, aseptic city, whose sole alternative, apparently, is the artificial experiential space. The newly emerging brand worlds, hence, are also characterized as places of re-enchantment [Sellmann/Isenberg 2000] to which a spiritual surplus may be attributed, [Bolz 2003] in the sense that they accommodate moments of the spiritual, of the non-logically deducible, within the disenchanted world of Modernity. Or, as Situationist Gilles Ivan has characterized the task of a future urbanism: “A rational expansion of the old religious systems, the old fairy tales, and especially psychoanalysis, becomes more urgent every day, to the degree that passion increasingly vanishes. Everyone will, so to speak, occupy his own cathedral. There will be spaces that permit better dreaming than drugs; houses in which one can only love (…) The quarters of this city could correspond to the catalog of the various feelings encountered accidentally in the normal course of living.” [Ivan Chtcheglov (Gilles Ivan), ‘Formular für einen neuen Urbanismus’, in I.S. NR 1, cited in Levin 1998, p. 71] Would not such a city be the dream of any urban marketing?

Misappropriation and fakery as marketing illusions

As one of their methods for bringing a Situationist city into being, Debord and Wolman developed the strategy of détournement, of reversal and misappropriation. Détournement relates both to objects and to spaces, to actions as well as to methods of perception. The core of détournement is to tear an object from its original context and to situate it in a new one, but in such a way that it still refers to its original context, with this multiple referentiality making new modes of reading possible. Détournement takes place when someone, to use a famous example, wanders through the Harz Mountains carrying a city map of London. “All elements, no matter what their sources, can become objects of new contexts.” [Debord/Wolman, ‘Gebrauchsanweisung für Zweckentfremdung,’ 1956, cited in Levin 1998, p. 73] The strategy of détournement can be understood, then, as a means of communication that serves, through reversal and irritation, to convey critical new contents and to subtly enable novel experiences. Subterfuge and irritation are essential functional mechanisms. Out of the strategy of détournement, developed in the 1970s, evolved the fun and communication guerilla [cf. Blisset/Brünzels 1998, p. 65ff], who made the fake an important element of action-oriented media and social critique. “A successful fake plays with the classifications of author and text. Its effectiveness unfolds precisely where it permits no unambiguous references to emerge: At this moment, the meanings of the affected statement begin to oscillate, and new interpretations become evident and available. With the fake, the principle of interpretative variability, which acts in conventional processes of communication as an unavoidable disturbance factor, is the foundation that makes the fake’s mode of communication possible in the first place. The fake wants not to be taken literally, but instead to trigger reflections about the originator and the content of the message.” [Blisset/Brünzels 1998, p. 67].

The Situationist strategy of the fake and of détournement can be discovered as an instrument of communication in nearly all of Nike’s urban interventions. They serve here the same function as they do with the Situationists and media guerillas, namely to gain access to new spaces of interpretation and opportunities for reflection.

But with Nike, the brand stands in the foreground, not the political statement. The signs on the Bolzplätze, with their interdictions (‘Enter at your own risk’; ‘No bottles’) are intended to trigger exactly the same mechanisms in the target group which Blisset/Brünzels have described as the effects of the fake. This strategy is found in multiple forms in Nike’s campaigns, whether on posters (“There are more ball courts than you think. One of them is right under this poster.” Niketown opening, 1999), or in Happening style actions. As when a group of young artists (accompanied by the requisite media) stormed Berlin museums to install posters reading “Down with the Spanish champions.” Here, the soliciting of public attention follows the pattern set by the media guerilla, and observers may well have believed these were in fact young artists attempting to come to terms with the museumization of art. But the group storming the museum were actually paid actors hired by an agency to install advertisements for a soccer match between the club Hertha BSC Berlin, sponsored by Nike, and FC Barcelona – the Spanish (soccer) champion.