Beside the large social change of mindset, is there some material aspect to feminist city, some concrete urban improvements we could initiate?

It has to be a combination of what we might call ‘urban spatial interventions’ and also social interventions. I mentioned creating the kind of social safety net that allows women and other vulnerable people to have a measure of economic independence and stability preventing them from having to be in dangerous situations. That’s crucial, but in the city itself we can also imagine very obvious things such as improving the lighting and walkways, having the kind of spaces where, as Jane Jacobs famously said, there are ‘eyes on the street’, where there’s a community, where there’s a vibrant public life at different times of the day, where people are able to look through their windows and see what’s going on in the community, where people know their neighbors so we don’t have quiet and abandoned spaces. People often express that they feel fearful of homeless people, but the solution to that is not to move them out of the city, rather to give people homes so that they are not forced to live on the street and engage in activities that may make other people afraid of them. It has to be this combined approach where we have a good social safety net as well as an urban environment that is open and welcoming to as many people as possible.

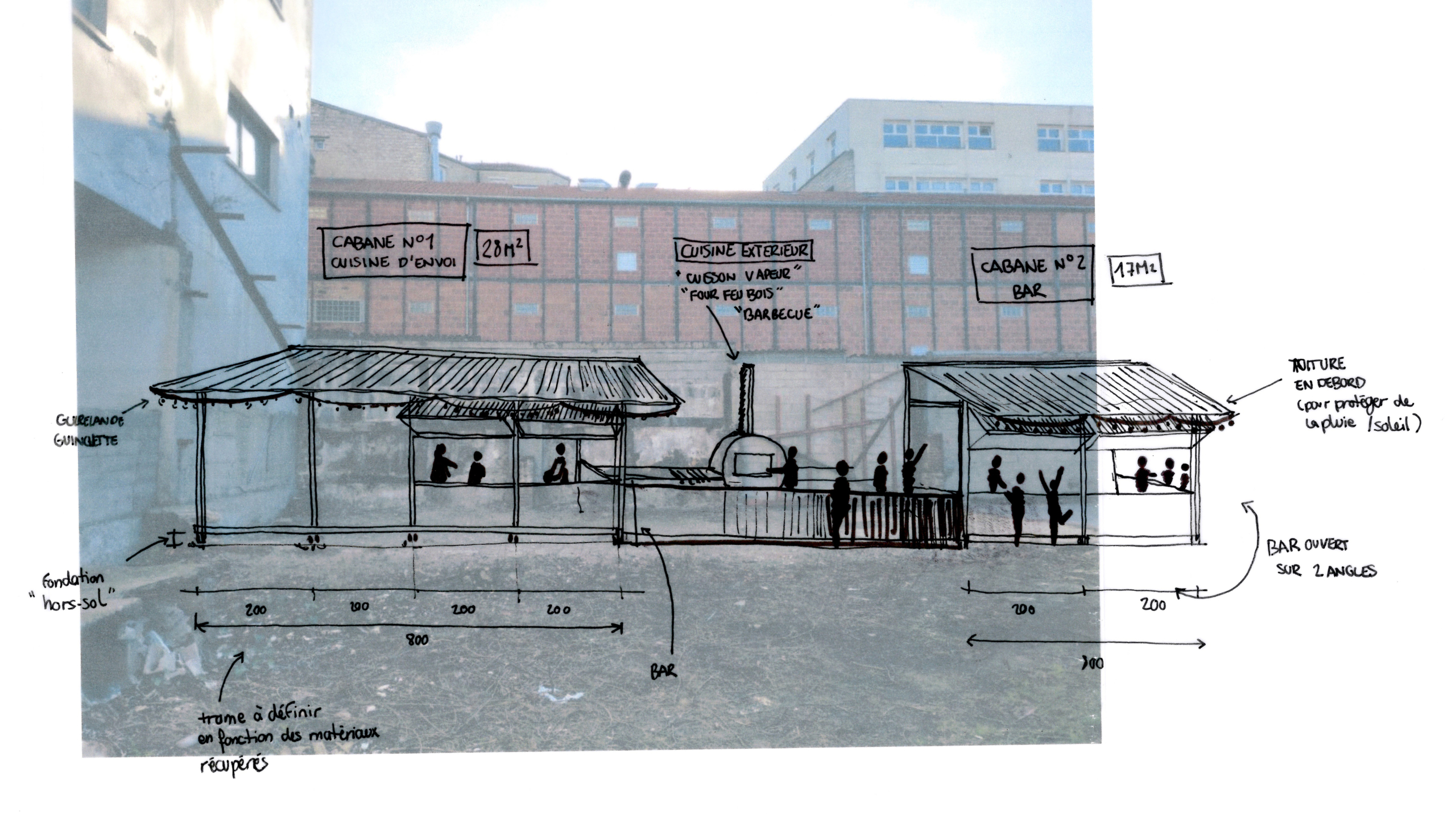

Improving lighting provides a good example of a holistic approach: on a basic level, it seems to go against environmental energy conservation measures, but we have to consider this within the broader issue of the kinds of neighborhoods we create. We don’t need bright, glowing lights everywhere if we do have a variety of mixed uses on the street with homes, businesses and cafes, shops, public transportation, and so on, and such a configuration would feel much safer to people than even a well-lit but abandoned street. Being alone is the greatest factor for fear. We have to rethink the way cities have been designed to separate work in one zone, homes in another, industry or shopping in another. If we have more mixed-use spaces, people are out and about, and they feel comfortable in the presence of others. In Paris, the mayor has been talking about the 15-minute city, and that concept certainly relates to feminist ideas about bringing those things to gather and creating more proximity of services, which could also help with the care work burden. At least, as long as we address the question of who can afford to live in these 15-minute neighborhoods.

It’s the same with smart technologies. In some cases, women have been making use of technology like mobile apps to stay safe, tracking places of harassment and fear for instance. This can be a useful thing, but in many cases we know that these technologies, just like the city, are not neutral. They’re designed by particular people, and they might not serve the needs of a majority of users, and there’s still a technology divide in who has access to a smartphone or a computer at home. Not everybody has access to those things, so it’s likely to lead to skewed data in terms of what gets input into the system based on who has the technology and from which information is being gathered.

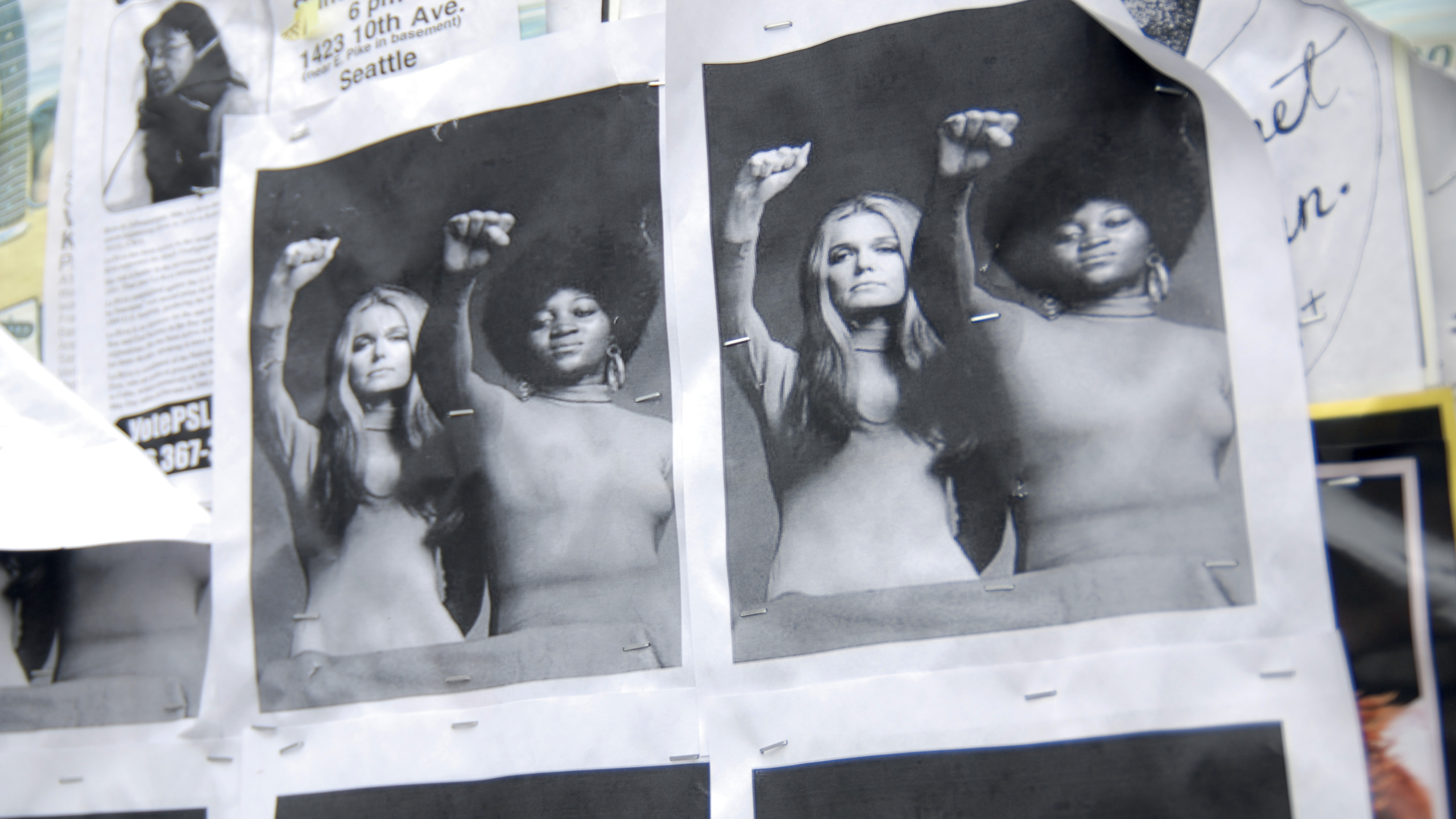

One of the great things about cities is that there are so many different communities and neighborhoods in them that have long been generating their own ideas about what they need and what works for them. I would like to imagine that we can pay attention to those communities and listen to what they actually need. For many cities over the last several decades, the goal has been to use urban space to create as much capital accumulation as possible. So it is also about a greater mindset shift away from thinking about cities as profit-generating machines to thinking about them as viable.

The involvement of community is key in many aspects of the gendered and inclusive approach you describe. Do you think it should inspire a shift from top-down to a more bottom-up approach of urban planning?

A bottom-up approach is definitely key. It’s challenging because it does take more time for planners and developers to consult with the community, to really listen to people, to find ways to engage a wide variety of community members who might not feel that they should go to a planning meeting, or don’t think that they can have their voices heard by the people in power. So it’s a slower process. It’s not always easy to give communities everything that they want, but as someone pointed out to me once, it actually will save you time and money in the long run, because if you design a space that nobody wants to use, or is unsafe, or becomes a haven for dangerous activity, or isn’t sustainable in some way, then you have to rebuild it. And this is much more expensive than just taking the time from the beginning to create the kind of housing, or playground, or green space, or transportation routes that would actually serve the people in those communities.

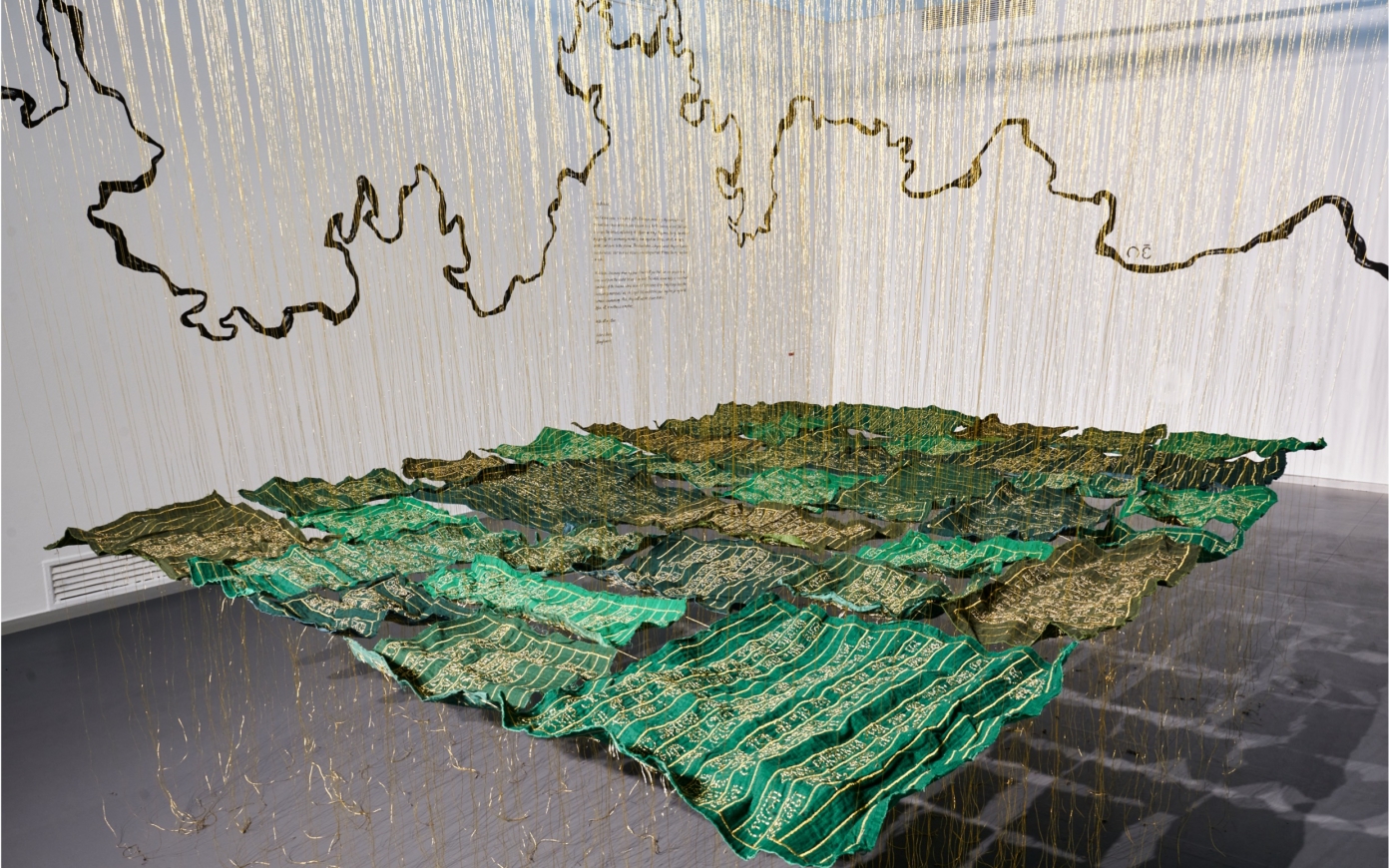

With the pandemic, we’ve also seen communities really taking matters into their own hands in terms of creating what we call ‘mutual aid practices’, which is where you are making sure that the people in your neighborhood have enough food to eat, where you’re checking on senior citizens, where you’re helping to look after each other’s children when it’s safe to do so, when you are giving people rides to and from work or Covid tests, these sorts of things. Communities have long found ways to create their own networks of care. I think that if we pay attention to and start to look for what is already happening, we can learn a lot about how we might scale those things up and learn where our cities need to do better to provide for the needs of people who are vulnerable in our cities. It’s just a question of what we decide to make a priority for our society.