Our aesthetic is deeply informed by the ways in which nature works, including the many connections, organizations, and structures that exist beyond and below human scales of space and time. In this regard, we draw from complex adaptive systems theory and other research in systems and simulation that follow nature by analogy and mechanism. From our earliest and simplest sketches, we built worlds as systems, grounded in shared resources and processes. Our goal is not to make creatures, but ecologies. (We have been asked, “Could your creatures one day escape?”, but the creatures cannot exist outside their environment any more than humans can escape Earth without bringing and sustaining enough of the biosphere with them. It’s not about individuals escaping, it’s about the system.)

“Near-lives”, at the limit of “nature” and “artifice”

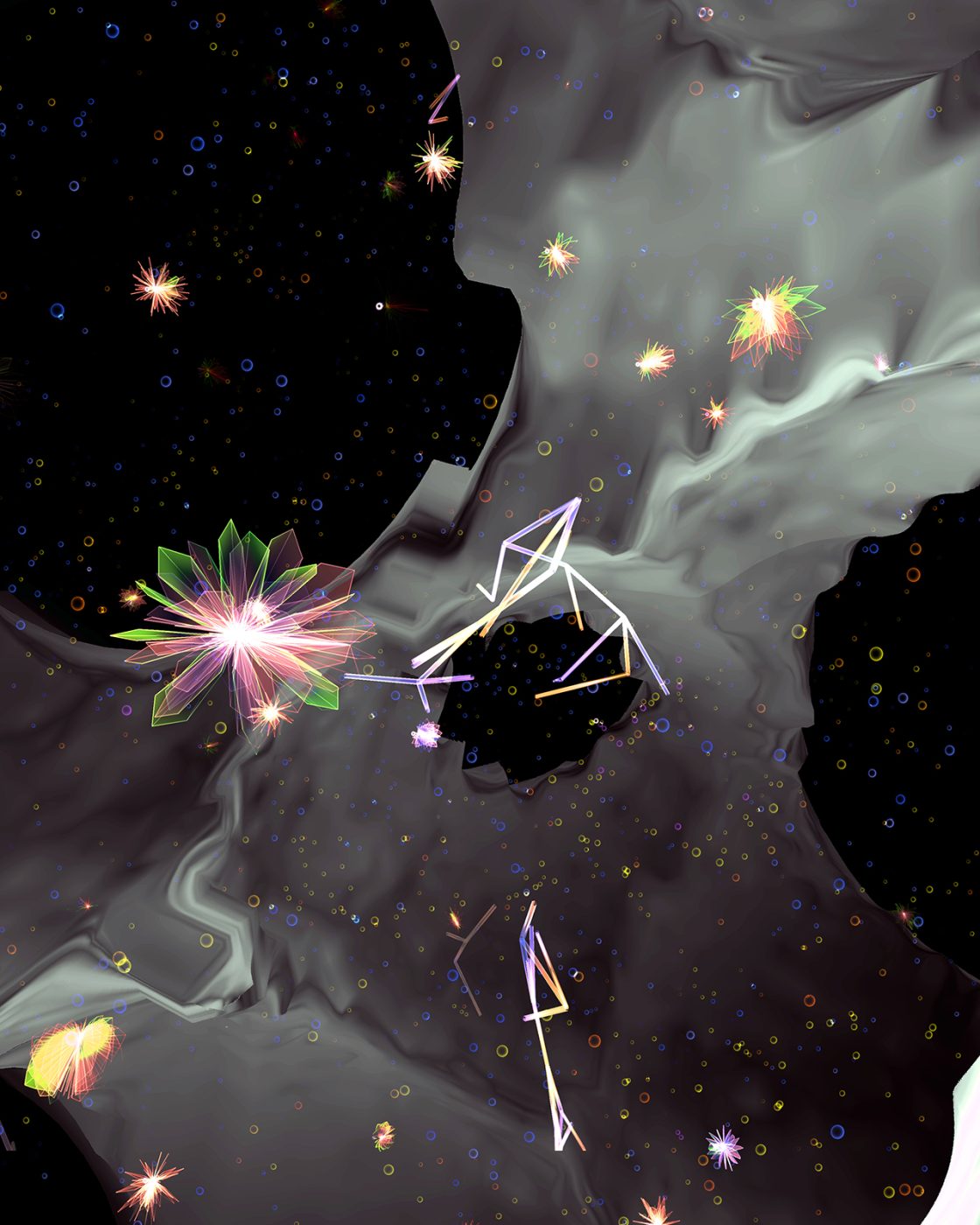

We program the interfaces and boundaries of this world, its conditions and regularities, many of which are probabilistic and sensitive to human interaction. But it is not entirely pre-programmed nor random. Between these limits there is enough space for organisms to develop themselves as self-determined individuals, creating their own rules and limits as they adapt to their changing world. Creatures may have inherited characteristics, in forms far simpler than nature’s DNA, but which nevertheless regulate variations in the behavioral and morphological patterns of each individual. Sometimes these adaptations are shared within lifetimes like bacterial horizontal gene transfer; sometimes adaptations are expressed rapidly at group level like viral quasispecies.

As Henri Bergson pointed out one century ago, the tendency of the non-living is toward similarity, stasis, symmetry, and predictability, such as the assimilating limits and averages of entropy. Subverting these conditions, the tendency of the living is to create new tendencies, new asymmetries, new senses, new qualities. A world making itself within a world unmaking itself. To incorporate a near-living capacity into our works implies increasing the rate of rare events— events whose primary discernment is in breaking bounds, thus resisting quantitative simplification and prediction—without simultaneously diminishing their rarity. As such, the creativity of life isn’t a pre-defined problem amenable to preliminary optimization. Life is what differs from itself, continually rewriting itself into new regimes. Fortunately, rewriting, and the generation of new rules as code, is fundamental to computing—it is this unconventional “second order” capacity that makes computing possible in the first place. To this end we have employed run-time code generation: each time an organism is born (often hundreds of times per minute), we generate a new program for it, based on its uniquely mutated genetic inheritance, and convert this program to native machine code for speed.

An interactive work to experience the complexity of an ecosystem

It is important to us that the complex network of feedback relations in the world envelops the visitor, in display and interaction, and brings the generative capacity of computation into an experiential level reminiscent of, yet different to, the open-endedness of the natural world.

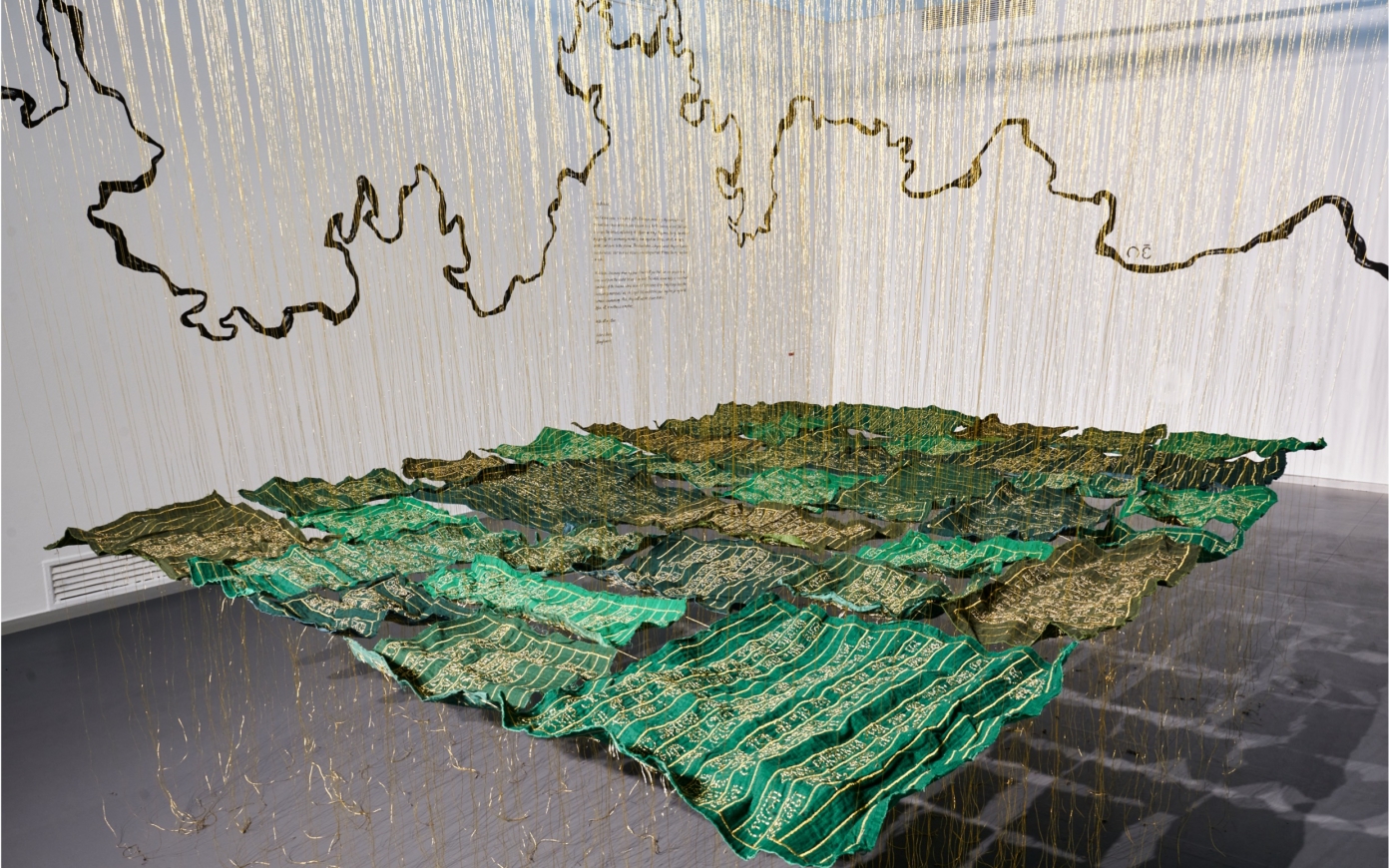

It is hard to understand the complexity of an ecosystem in all its relations and flows from a series of singular views. Therefore, we have found our works have become more intentionally plural. “Time of Doubles,” for example, realizes the coexistence of multiple “doubles” in mirrored worlds; whereas “Inhabitat” realizes the coexistence of multiple worlds in the same physical space, as well as multiple perspectives in the same time: first person, second person, and impersonal.

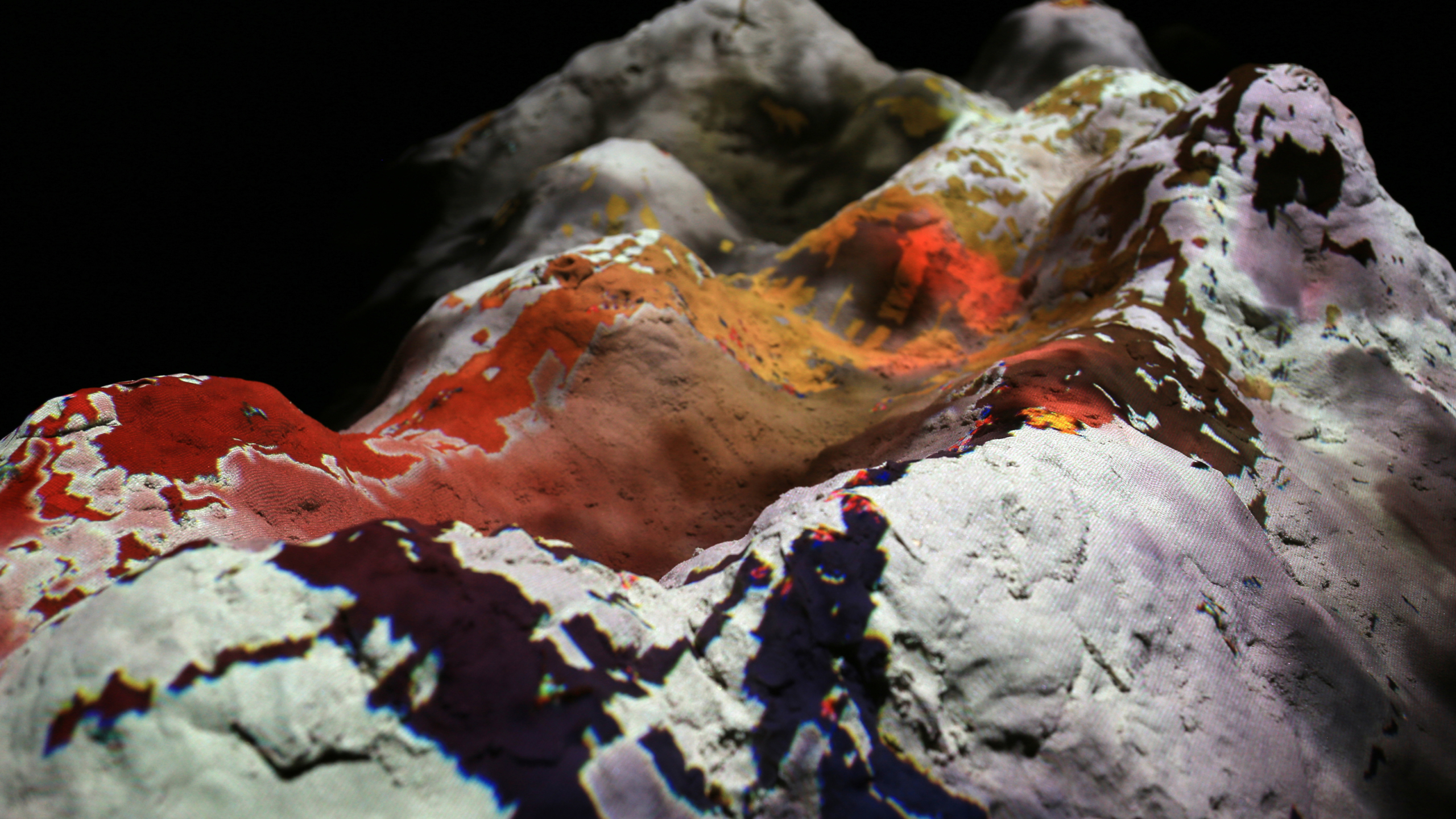

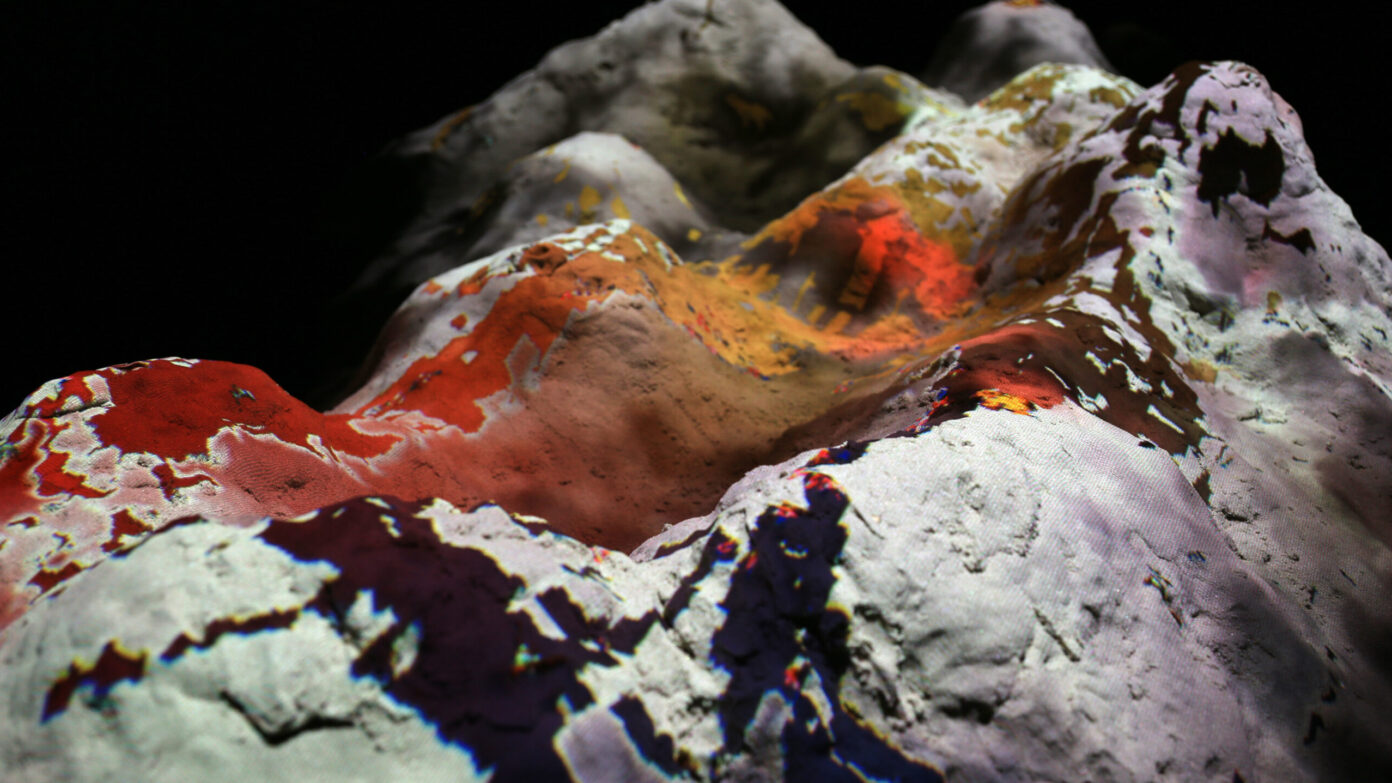

We use continuous and indirect modes of interaction where possible, preferring polyvalent bidirectionality over symbolic cause-and-effect. The organisms grow and adapt to an environment in part shaped by you: perhaps your body influences currents of the wind, perhaps your virtual self is eaten by them. Interactions are also often both destructive and constructive in nature. In “Archipelago” for instance, your shadow under the projectors is calculated and regenerated in order to grant it an ontological force in the world: it destroys the vegetation underneath it at the base of the food web. You are literally a force of darkness, but also of rebirth. Rather like a wildfire, after destruction the land bounces back more fertile than before. As much as you are a destroyer, like Shiva, you are also a creator.

But if you feel you are a god to the virtual world, you are far from omnipotent. The interaction is highly responsive and nuanced but your influence is limited in range. The world welcomes you into itself at a high level of detail, but it will also continue to thrive without you. You may become a significant part of an ecosystem, but not in a singular role, and not as the main subject. For us it is important to displace the centrally-privileged position of the human as just one example of all possible lives. In this view, the world becomes bigger.