Art and Agency in Times of Wetware

- Publish On 18 November 2017

- Jens Hauser

Faced with an obsessive questioning about the nature of life, art has tried to understand and recreate the living, developing the myth of “revival” and a fascination with the staging of the living. Having always sought to imagine, represent and imitate, then simulate the living, it now manages to manipulate it directly via wetware. If information technology provided art with a new direction in the seventies, favoring dynamic processes rather than objects, the convergence of synthetic biology and technologies of the living that now allow us to explore this wetware, “wet machines”, blurs the borders between organisms and machines. The creation of “artificial life” goes beyond computer simulations and robotics, giving birth to hybrid and semi-living systems that challenge the boundaries between the living and the non-living, between synthetic and organic life. For the Artificial life art, organic simulation and re-materialization are no longer distinct but rather operations that are compatible with wetware, shifting concepts of art, agency and animation.

Primitive Technicity and Animated Encapsulations

However, when foretelling What is Life? in the future, we may consider not only the standardization and modularization of abstract units similar to hardware and software, transposed to wetware, but also ask – as anthropologist Stefan Helmreich does – What was Life?Helmreich, Stefan: What Was Life? Answers from Three Limit Biologies. In: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Summer 2011), p. 671-696. Would we discover the future of possible forms of life in the rear view mirror of how life originally emerged in the realm of what Helmreich calls ‘limit biologies’? If ‘life’ as a concept is above all “a pattern transposable across media,” Ibid, p. 676. then we may take a closer look at the extreme ecologies of ocean life, such as in phytoplankton, or at the ability of bacteria to survive extreme conditions: “Limit biologies like ‘Artificial Life’, extreme marine biology, and astrobiology point to larger instabilities in concepts of nature – organic, earthly, cosmic,”Ibid, p. 677. of aliveness as such. What is more, one will find at these limits a whole range of phenomena that can be addressed as the innate technical capacities of microorganisms when “pressed against the boundaries of what biologists believed living things capable of”Ibid, p. 683. – ‘nature’ that itself engineers and synthesizes, so to speak, including bacteria evolving to eat plastic or other man-made trash.

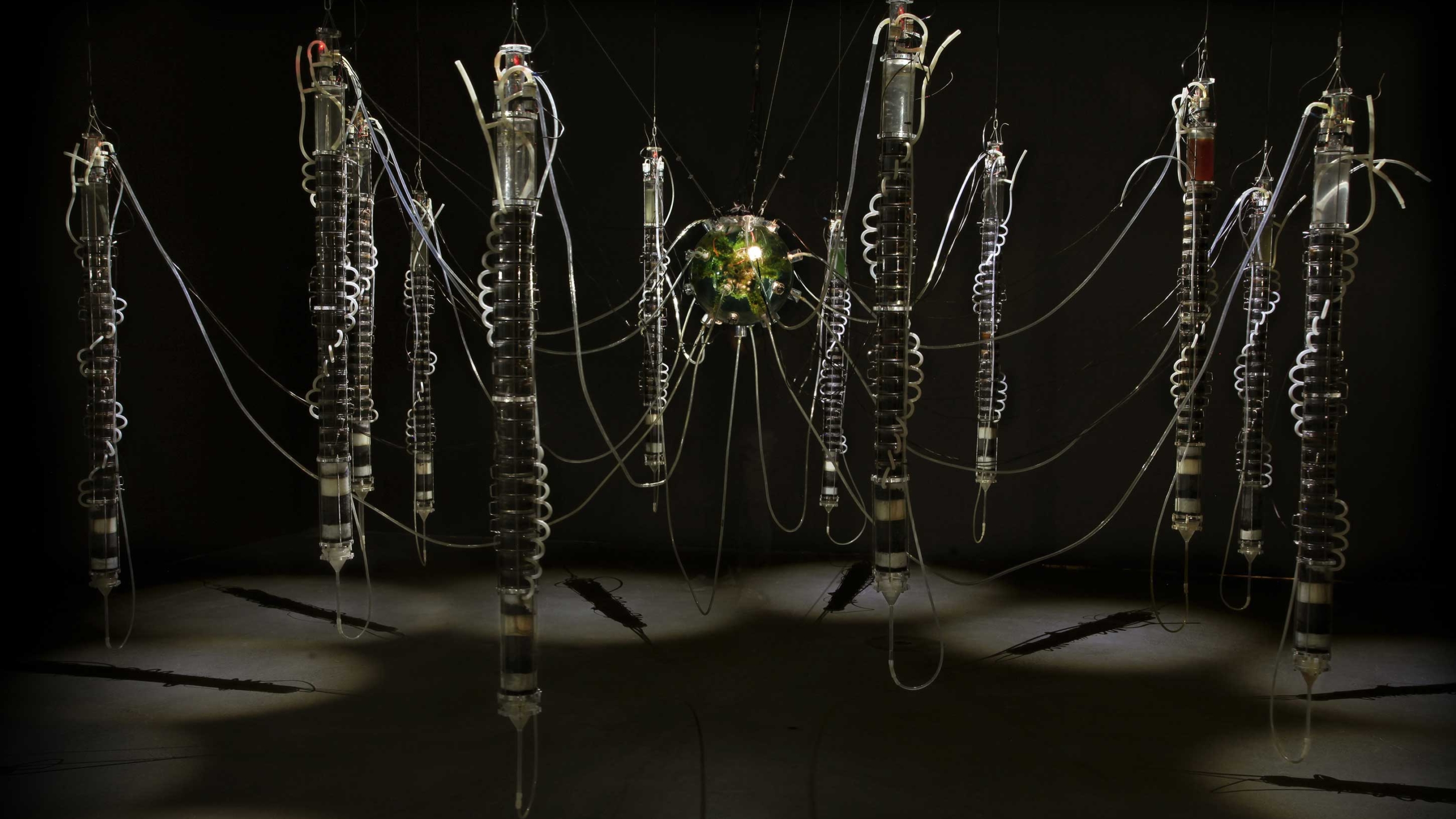

Wetware art embodies and poetically materializes such philosophical and epistemological questions. For example, Mexican artist Gilberto Esparza’s practice emblematically reflects on life as a pattern transposable across media, shifting notions of Artificial Life from the mechanical, electronic and computational back to the organic realm. The visitor encounters somehow familiar, buzzing diptera defending their living space with their inexhaustible, somewhat too steadily circling rotor blades, tied to thin electric cables. Giant caterpillars appear to have caught their teeth on telephone wires, burrowing their way into and hampering telecommunication, and multipeds with cylindrical torsos and delicate limbs do away with the waste of urban civilization – all these soft and hardware Parasites are exclusively constructed out of humankind’s technological waste. By contrast, Esparza’s BioSoNot presents itself as a musical synthesizer that allows humans to hear electrical oscillations of bacteria in microbial fuel cells as they clean contaminated water – and, as a matter of fact, the artist uses autochthonous ‘naturally synthesizing’ bacteria only, not engineered ones. In the same vein, Adam Brown’s Great Work of the Metal Lover hosts extremophile bacteria, often used in ecological remediation to filter toxic metals out of industrially polluted soils. Here, they produce gold, thereby seeming to solve the alchemist riddle of the philosopher’s stone. Such procedural art works express less the ‘autonomous’ and ‘intelligent’ behavior, often claimed in earlier A-Life art to describe the mimicking of human cognition, but rather their systems’ decentralized and collaborative intelligence to clean up humankind’s mess in times of major ecological and atmospheric crises.

Meanwhile, the Panama disease is threatening the Cavendish, the world’s most popular banana, and Orkan Telhan constructs a Microbial Design Studio – a countertop wetlab to engineer bacteria at home that can reproduce Cavendish’s smell and taste in semi-living encapsulations. Another type of encapsulation is the key element in Evelina Domnitch and Dmitry Gelfand’s live installation Luminiferous Drift. Considered bottom-up A-Life, so-called protocells – models of cells formed by an innate, complex chemistry – visualize physically simulated movements of phytoplankton in a biosphere as seen from space, thus impressively materializing the fragility of our ecosystems and biospheres at a miniature level. One ‘limit biology’ models another in an interplay of non-human actors that carry out a dazzling spectacle of what can be called microperformativityHauser, Jens: Molekulartheater, Mikroperformativität und Plantamorphisierungen. In: Stemmler, Susanne (ed.): Wahrnehmung, Erfahrung, Experiment, Wissen. Objektivität und Subjektivität in den Künsten und den Wissenschaften. Zürich/Berlin, 2014, p. 173-189..

Microperformativity and Macroconcerns

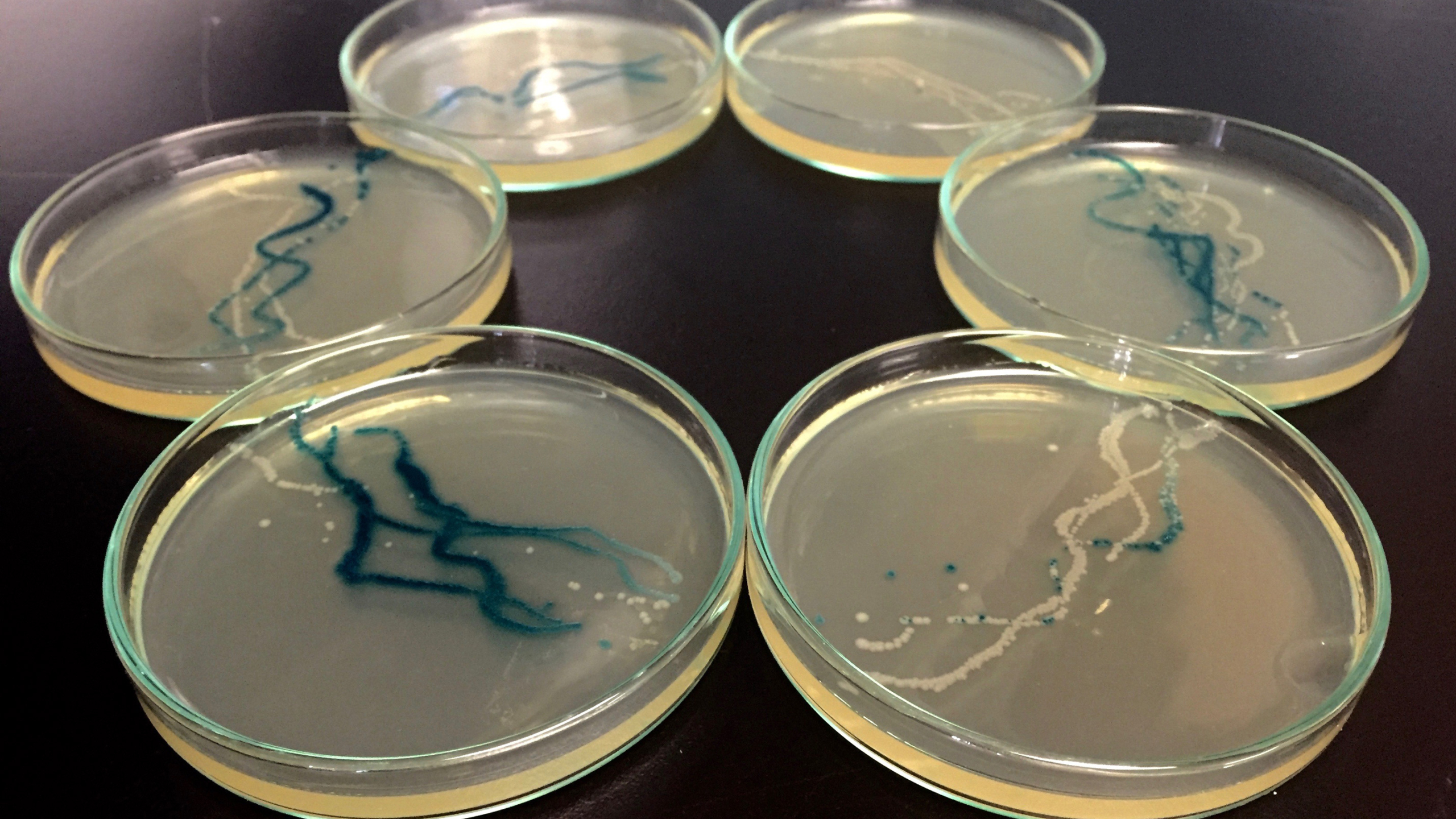

In Klaus Spiess and Lucie Strecker’s biotechnological stagings, microperformativity also plays a central role. For Hare’s Blood + a ‘molecular animal’ has been designed in the form of an engineered artistic biobrick, a standardized genetic sequence incorporating gene sequences isolated from the blood of Joseph Beuys’ famous hare, and turning the politically engaged happening artist’s utopia of an equitable counter-economy upside down, in light of the current speculation in bio parts. Engineered bacteria, then, are the protagonists of Thomas Feuerstein’s biotechnological sculpture Pancreas – wetware in the most literal sense used in science fiction and denoting functional elements equivalent to a computer found in biological systems or in a person – here, in the human brain. Feuerstein refers to another connotation of wetware, namely that “in comparison to hardware and software, wetware is a somewhat dysfunctional component, first and foremost a source of errors [and] may be blatantly inferior, but some of its interior aspects are – still – unattainable to hardware and software.”Winthrop-Young, Geoffrey: Hardware/Software/Wetware. In: Mitchell, W.J.T. and Hansen, Mark B. N. (ed.): Critical Terms for Media Studies. Chicago/London, 2010, p. 191. Touching upon the brain’s position between spiritualism and metabolism, the artist feeds human neuroglia cells with glucose to grow into the shape of a human brain, thanks to specifically modified bacteria that produce glucose by breaking down cellulose from shredded books. However, the feeding of the artificial brain follows a strict diet since it exclusively consists of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit: ‘Food for thought’ becomes ‘thought for food.’

Anna Dumitriu’s lab investigations into synthetic evolution and non-canonical amino acids focus on the interplay between abstract modeling and three-dimensional wetware folding of amino acids in antibody research, while questioning biology’s terminology and heuristic metaphors, such as the image that all forms of organic life are made of amino acids that join together like strings of beads. Here, the object of presentation and the mode of representation become one and the same: In Engineered Antibody, a beaded necklace, human size, both represents and physically contains the actual 21 amino acids of an antibody – in Necklace, then, Dumitriu relocates and miniaturizes the ‘string of beads’ metaphor at the actual genomic level: engineered, circular plasmid DNA sequences are themselves considered the ‘necklaces’, but ‘worn’ inside the bacterium itself this time.

Micro-sculptures of this kind invoke historical precursors, such as Jack Burnham’s writings on “The Effects of Science and Technology on the Sculpture of this Century.”Burnham, Jack: Beyond Modern Sculpture. The Effects of Science and Technology on the Sculpture of this Century. New York, 1968. Held in high esteem in media art circles as influential ‘guru’ reading, the book is unfortunately overlooked in classical art history. At the very moment Lucy Lippard diagnosed the period of the “dematerialization of the art object”Lippard, Lucy R.: Six Years. The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. New York, 1973. with its greater focus on ideas and actions, Burnham provides a retrospective, biologistic and informed by the history of technology, of over 2500 years of sculpture, arguing that its very ‘survival’ is dependent on its transition from material objects to complex systems: from idealistic-vitalist imaginary shapes to organicistic processes in which macro phenomena of the living are explained by underlying micro phenomena, a transition “of sculpture from a psychically-impregnated totemic object toward a more literal adaptation of scientific reality via the model or technologically inspired artifact,” therefore towards “life-simulating systems through the use of technology.”Burnham, ibid., p. 7. Influenced by cybernetics, and the modern genetics it inspired, but also by environmental concerns, as well as the early systems biology of Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Burnham calls for a departure from form and a reorientation toward functionality in sculpture of the future “away from biotic appearances toward biotic functioning via the machine.”Burnham, ibid., p. 76. He hopes that spectators of such art would be stimulated to adopt a planetary-holistic environmental consciousness – not contra but qua technology:

If man is approaching a time of radical change, one not controlled by natural selection and mutation, what better nonscientific way exists for anticipating self-re-creation (not procreation) than the spiritually motivated activity of artificially forming images of organic origin? Could it be that modern sculpture is this process vastly accelerated?Burnham, ibid., p. 374.

Against this background, then, it is even more plausible why Burnham became the initiator of the seminal Software show in 1970 in New York. Despite the far-reaching technological advances experienced since that time, many of the exhibition’s claims take on unexpected pertinence today. While overcoming distinctions between art and other cultural practices deeply influenced by new information technologies, Burnham also anticipated art’s general move towards “concerns with natural and man-made systems, processes, ecological relationships,”Burnham, Jack: Notes on art and information processing. In: Burnham, Software, ibid., p. 10. picking up the assumption that if “we build machines in our own self-image […] a separation between body and mind may be no more than an illusion fostered by our lack of scientific knowledge about human biology and communication systems in general.”Ibid., p. 11. The influence of the, then, rapidly developing information processing technology “on notions such as creativity, perception and art”Ibid. reaches a new level in man-made ‘wet machines,’ and it is worth noting that Burnham himself claimed that, in fact, “the division between software and hardware is one that tangibly relates to our own anthropomorphism,”Ibid. and that needs to be overcome. He also pointed to two other features that become relevant again in Wetware: “the steady trend towards democratization,”Ibid., p. 13. when technologies which two decades ago still were only accessible to a highly skilled elite become tools for laymen in short time, and the challenges that arise when such practices update older definitions of art, since “ars in the Middle Ages was less theoretical than scientia: it dealt with the manual skills related to a craft or technique. But present distinctions between the fine, applied, and scientific arts have grown out of all proportion to the original schism precipitated by the Industrial Revolution.” Therefore, Software made “none of the usual qualitative distinctions between the artistic and technical subcultures.Ibid., p. 14.

In light of the recent DIY biology trend, on the one hand, and the hype around synthetic biology, on the other, it is surprising how visionary such statements sound four and a half decades later – a nearly incommensurable time span, if not an eternity, in terms of Moore’s law! According to Intel co-founder Gordon Moore’s observations and predictions in the 1960s and 1970s, the number of transistors per chip that result in lower prices per transistor and drive a profound technological and socio-economic – and consequently, as we know, cultural – change, would double approximately every two years. Today, however, it seems that the semiconductor industry is no longer catching up with these predictionsMitchell, Waldrop M.: More Than Moore. In: Nature, Vol. 530, (11 February) 2016, p. 144-147. and that the “Moore’s law really is dead this time,”Bright, Peter: Moore’s law really is dead this time. In: Ars Technica, (11 February) 2016; http://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2016/02/moores-law-really-is-dead-this-time as a result of such problems as heat in ever smaller chips and quantum physics phenomena when attempting further miniaturization no longer achievable with conventional materials. Is wetware the way out? Many anticipate the still underexplored promises of fluid, chemical and wetware computing on the basis of cells, DNA, neurons etc.: “Never mind tablet computers. Wait till you see bubbles and slime mold!”Popkin, Gabriel: Moore’s Law Is About to Get Weird. Never mind tablet computers. Wait till you see bubbles and slime mold. In: Nautilus, Issue 21, “Information. The Anatomy of Everything”, (12 February) 2015; http://nautil.us/issue/21/information/moores-law-is-about-to-get-weird In the arts, with all its aesthetic and technical subcultures, it is definitively time for a wetware update.