You are a science historian and you have worked on the role of images in conceptualizing a new world in the seventeenth century. Can you explain to us how this analytical framework, applied through a history of representation and science, can help us to understand the current revolution?

This is a compelling question as it immediately suggests a parallel between the cosmological upheavals experienced in the seventeenth century and the one we are experiencing today, a connection which is actually far from obvious. I share with Bruno Latour this idea that we are undergoing a cosmological shift as fundamental as the Copernican Revolution. This parallel is foundational and inspiring for my work. My research explores the role and power of images in the construction of this form of new understandings of the world.

Take the example of heliocentrism. More than a century elapsed between the theory of Copernicus—placing the Sun rather than the Earth at the center of the universe—and its demonstration by Newton made possible by new optical and algebraic instruments. During this interval, the proposal was not demonstrated. It was instead abundantly illustrated through pictures and celestial travel stories, which gave to see by the imagination what the science of the time could not yet show and demonstrate. It is thus by the fiction and the representation that the upheaval takes place. Images are key to scientific discoveries and their role goes well beyond mere illustration In this sense, they prefigure the transformations of our relationship to the world.

My initial background was in literature before I became interested in the history of science. This disciplinary shift helped me analyze various images which had a decisive role in scientific progress. I am thinking in particular of images in the rhetorical sense of the term. Those of ekphrasis, that is the way in which words bring about to a mental representation. Somnium: The Dream, or Posthumous Work on Lunar Astronomy is a good example of this. A fictional work written by astronomer Johannes Kepler, it describes a journey to the Moon, from which the Earth can be seen to turn on itself in the distance. This extremely vivid image played an important role in the debates of the time. Then, there are the engraved or drawn images following the tradition of lunar maps and various representations of the cosmos. I particularly like Andrea Cellarius’s atlas, which is one of the first colorized astronomical atlases and which depicts different cosmological systems conceived by man over the centuries, including the Ptolemaic system, which represented the Earth at it’s center, as well as Tycho Brahe’s system, which mixes the old and the new cosmology but keeps the Earth in the center of the universe, and finally the Copernican system, which makes of the Earth a planet turning around the sun, like the other planets.

Today, if we look at the work of thinkers such as Baptiste Morizot, Emanuele Coccia, or Bruno Latour, we realize that the birth of a new revolution in philosophical and scientific thought is under way. However, it is no longer about a cosmological upheaval in the order of the planets, but one in which our entire cosmos begins to move. Suddenly, the world around us comes to life. Following on from James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis, these contemporary thinkers express the idea that the living layer of the earth, the “critical zone”—Gaia, even—is a place of interaction where the Earth produces its own conditions of habitability. This leads us to entirely rethink the relationship between the living and the “environment,” supposedly inert, which have long been distinguished and separated.

Our Cartesian heritage has led us to imagine a separate context, a framework within which “acting agents” operate, with humans occupying a predominant position among them. Today, if we consider that space is no longer a container, but that it is constantly produced by the living, that it is a relationship, an interdependence, something as alive as that which produces it, it becomes impossible to construct a grid of coordinates and represent it as a stable surface or medium. This marks a profound change in the relationship to space, which can no longer be perceived as a simple backdrop, a set, a cadastral surface, or a blue marble seen from above and afar. We are an inseparable part of this living planet, which implies making our gaze “land,” as Bruno Latour would say.

Numerous scientific elements, in particular via Earth system science (ESS), make it possible to measure this essential critical zone, these few kilometers where all living things are concentrated—there is indeed no life, either above or below—and interconnected to all resources. Though the idea of Gaia sometimes leads to some reluctance, due to its mythological dimension, there is now a broad scientific consensus on this minimal definition of the critical zone—as with the notion of symbiosis, even though they might have seemed somewhat debatable hypotheses in the 1970s. However, we still have very few images of it. This is an interesting parallel with the Copernican Revolution. If the science is very advanced, it suffers however from a lack of representation of this “critical zone”. This is why, by calling upon art, theater, and cartography, we organized with Bruno Latour a performance entitled Inside, which we used to question the conventional representations of the globe, NASA’s Blue Marble, Earthrise, or the traditional representations of the cadastral type, with the ground seen as a surface. We sought to emphasize the limits of these modes of representation, to go beyond them, to begin exploring new images. In this case, art does not seek to anticipate, but to fill a lack of representation.

You mentioned the intersection of literature, science, and theater in Inside. How do you draw on tools from various disciplinary fields to raise awareness of this new perception of the Earth?

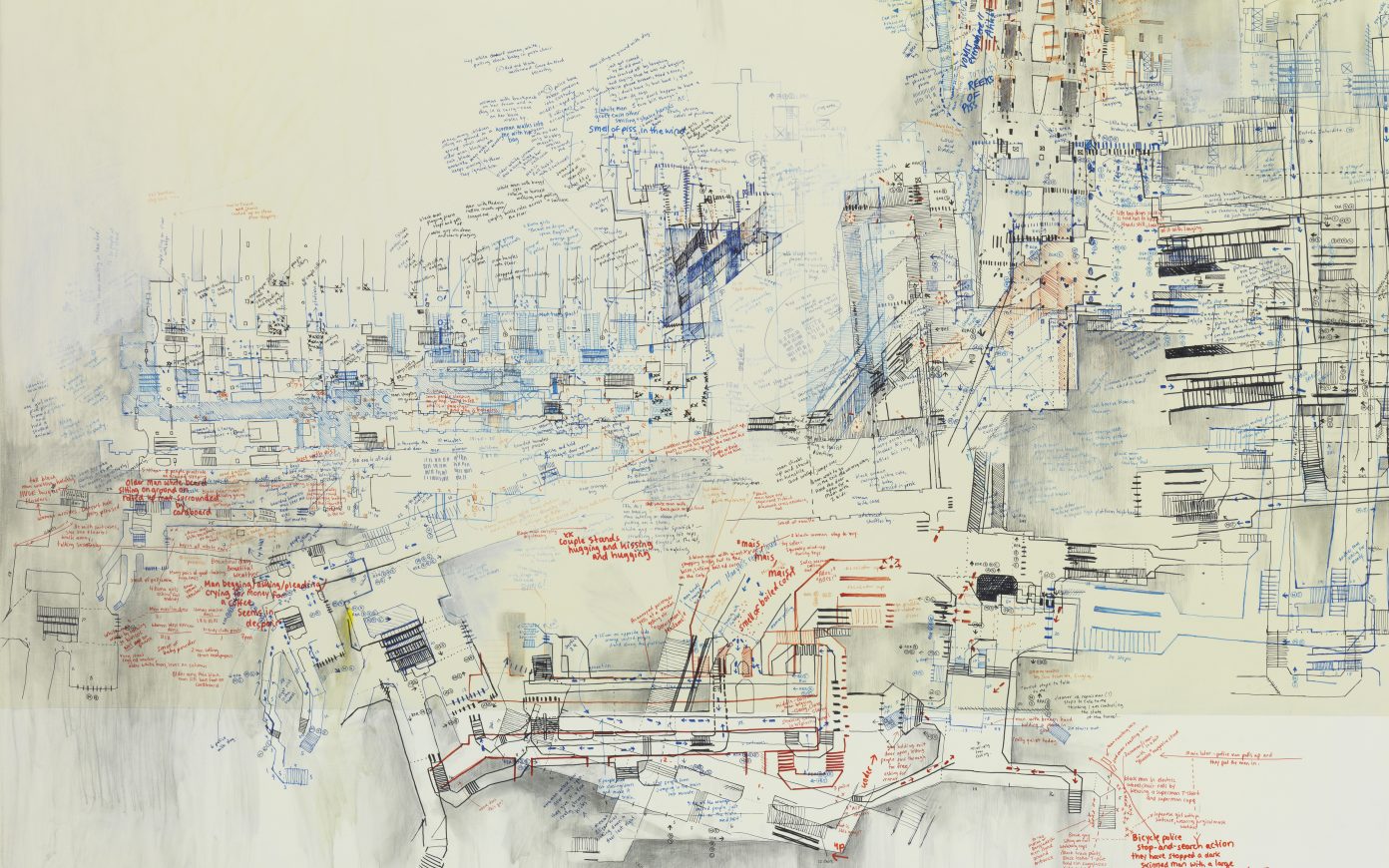

I obviously use my own tools—semiotics, rhetoric, and textual analysis from literary research—as well as those from the history of science and philosophy. The disciplinary question doesn’t really matter. What interests me is how we can draw on their intersections. I thus carried out a project with two architects—Alexandra Arènes and Axelle Grégoire—called Terra Forma, an atlas of potential cartographies which led us to deconstruct traditional cartographic to propose new, absolutely unique ones. Since every map follows conventions, we took it upon ourselves to alter the usual codes and cartographic conventions. Our goal was not to dismiss the old system of representations but to decenter it, to explore what images new conventions might produce.

Each chapter acts like a new lens on the world, proposing a model that leads to a new form of mapping. The atlas does not follow a single model, rather, it offers a different one for each subject, which makes reading it counterintuitive and somewhat unsettling. No sooner have you become familiar with a map’s frame of reference and legend than you have to relearn everything to decipher the next one. These maps therefore open up new optics and explore different ways of situating ourselves in the world.

To do this, we notably questioned the norms regarding the orientation toward the cardinal north of sectional projections, moving from a vertical, astronomical gaze to a horizontal, terrestrial gaze. One of the maps proposes placing the atmosphere at the center, where the Earth’s core would traditionally be represented, an anamorphosis which gives a greater emphasis to the living surface of the Earth, which in reality is only a thin film on its surface. We also sought to move from the eye to the body, in order to shift from the scopic view to that of the senses, and thus represent imperceptible things such as life paths, time, memory. This is based on the Coccian idea of “points of life” instead of “points of view.” We followed the trail of the living to cross the paths of a virus, a sales representative, a wild cat, and a nurse. To do so, we had to define the home ports of each territory of habits, basing ourselves on the model of portolan charts, the old navigation charts representing the winds, currents, or ports, but nevertheless devoid of datum or topography, thereby detaching them from any topological reference in space. We therefore return to classical or even pre-classical cartographic language in this atlas, while adapting it to a contemporary reading of territorial issues dear to us. Space is no longer a fixed and flat piece of data, but a shifting thickness, produced continually by those who inhabit it.

The collaboration with architects was essential to this project. While I offered models taken from history, Alexandra and Axelle came in with representational tools taken from architecture or landscape design. The atlas was thus constructed through a process of constant back and forth between each line written and each line drawn. Other tools were also borrowed from the so-called “hard” sciences—since nothing that is drawn is subjective or invented—which differentiates these maps from those proceeding from so-called “sensitive mapping.” Every parcel of information that is represented has been scientifically measured and quantified. For example, epidemiological models have revealed the trajectory taken by the virus, while the trajectory of the wild cat was established using sensors as part of Alexandra’s research, and the daily journey of a nurse was taken from a sociological survey. What was original in our approach was to combine these datasets from distant fields by freeing ourselves from scales in order to suggest other ways of showing data.

This methodology caught the attention of Jérôme Gaillardet, a geologist at the Institut de Physique du Globe in Paris. He then contacted us to suggest that we give the name Terra Forma to a vast European research project on the environment and the interactions between people and their environments. The fact that the concepts developed in our atlas of potential cartographies serve as a theoretical framework for a scientific project of scope clearly shows how representation can serve as a prerequisite for scientific advancement. This dialogue between art, science, history, and philosophy fascinates me. I am thinking in particular of a remarkable article co-authored by Timothy Lenton, one of the great Earth system sciences specialists, Bruno Latour, and Alexandra Arènes. They each need each other—and indeed without Alexandra there would be a lack of imagery, without Timothy Lenton, a lack of science, and without Bruno, a lack of philosophical implications. There is no better example of the interdependence of disciplines for me.

It is in this spirit of interdisciplinarity that you also are head of a Master’s program in Experimentation in Art and Politics (SPEAP) at Sciences Po, initiated by Bruno Latour. How is it distinctive in its teaching approach?

SPEAP is a Master’s program created by Bruno Latour in 2010, which I have directed for six years now. Through collective work and interdisciplinarity, the program aims to tackle scientific, environmental, and artistic questions by anchoring current controversies in political issues. In a sense, it is the “school” version of what we have just mentioned, since it is based on the involvement of students in concrete projects. We tend to throw the students “in at the deep end” by involving them in some of our projects which then, in turn, take on a collective and shared dimension. Last year, for example, we invited students to work on Bruno Latour’s Critical Zone exhibition, which was held at the ZKM in Karlsruhe. For my part, I try to involve the year’s cohort or previous cohorts in my work as a theater director. This was the case for the Inside performance-conference, which I referred to previously, but also for the other two parts of the terrestrial trilogy—Moving Earth and Viral, which I am currently preparing at the Nanterre-Amandiers theater.

Beyond the projects proposed by the faculty, the program’s concept is to work by answering questions formulated by public or private institutions. There is a theoretical syllabus, but commissioning remains the basis of our approach—with the underlying idea that a pedagogical approach cannot be detached from reality. Our patrons are extremely varied, including the Hospitals of Paris, Andra (an institution that manages the disposal of nuclear waste), CNES (a space laboratory), and the Urban Resources Exploration Center (PEROU) on migration issues, as well as the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris.

Alexandra, with whom we co-wrote Terra Forma, is a former student of SPEAP, and it is through a commission from the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris that she began to follow and trace the paths of living beings and how they intertwine as an alternative to the fixed representation of a given space. Within the Belval forest, which is located in the Ardennes and belongs to the museum, she carried out a project relating to the preservation and enhancement of biodiversity with an artist and an anthropologist. By reusing tools typically used by hunters, ethologists, and park managers, they produced an incredible map of the Domaine de Belval forest and its living beings, with data from a series of sensors, GPS signals, camera traps, etc. This was a sort of prefiguration of the Terra Forma atlas. The Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature was extremely pleased with this partnership, which resulted in an exhibition.

That said, it is important to emphasize that the SPEAP Master’s degree retains a freedom of outcome. It is essential that the project sponsors accept that these are exploratory, artistic, and collective works. Sponsors can propose a field and submit a problem, but cannot choose the members of the collective, the supervisors, or the production materials. Students are free to take any direction they wish and use the mediums that suit them to handle the topic, including video, a performance, a website, a publication, etc. This freedom is enabled by the fact that the expectations regarding the outcomes are closely connected to the financing context, and, in our case, that the investment is low or even negligible for the sponsors. We benefit from being in this educational framework as there are fewer specific expectations and less desire to control. The fact that it is unpredictable is actually quite attractive because this approach brings in an element of surprise and a much appreciated decentering, which often encourages institutions to renew their partnerships with us.

In my view, SPEAP isn’t a school in the sense of a curriculum running each year. It is one of my working environments, one of the territories I roam through, just like theater or research. These spaces intersect. I write with a community of thinkers, whom I invite to participate in my plays or who supervise certain SPEAP groups, including Emanuele Coccia, Baptiste Morizot, Vinciane Despret, and Nastassja Martin, to name a few. As for the students, they quickly become artistic or scientific collaborators. I’ve always struggled with hierarchy and generational differences. The imparting of knowledge from teacher to student is a very French model. I view the value of speech as being equal, whether you are eighteen or seventy-five. Alexandra is a good example of how SPEAP offers an incredible opportunity to meet young people with hybrid backgrounds and to foster scientific collaborations, even beyond the incubation period of the Master’s degree.

There is a French expression, faire école, which can be literally translated as “making school.” It implies not only creating a school of thought—assembling a following—but also suggests the idea of knowledge dissemination. In that sense, it seems to me that SPEAP has “made school” with its approach whereby it chooses not to base its pedagogy on a theoretical syllabus and is largely deterritorialized. I am happy to see that the principle of faire école has been taken up and spread across many parts of the world. Many art schools are interested in this kind of format and they are opening artistic education to other fields and addressing ecology, the Anthropocene, and political arts. I like to think that our Master’s program remained very small due to a lack of resources and time, but that it has been imitated and adapted in many ways.