Given that you describe yourself as a géoverrière (or “geoglass artist”), can you tell us what that discipline covers?

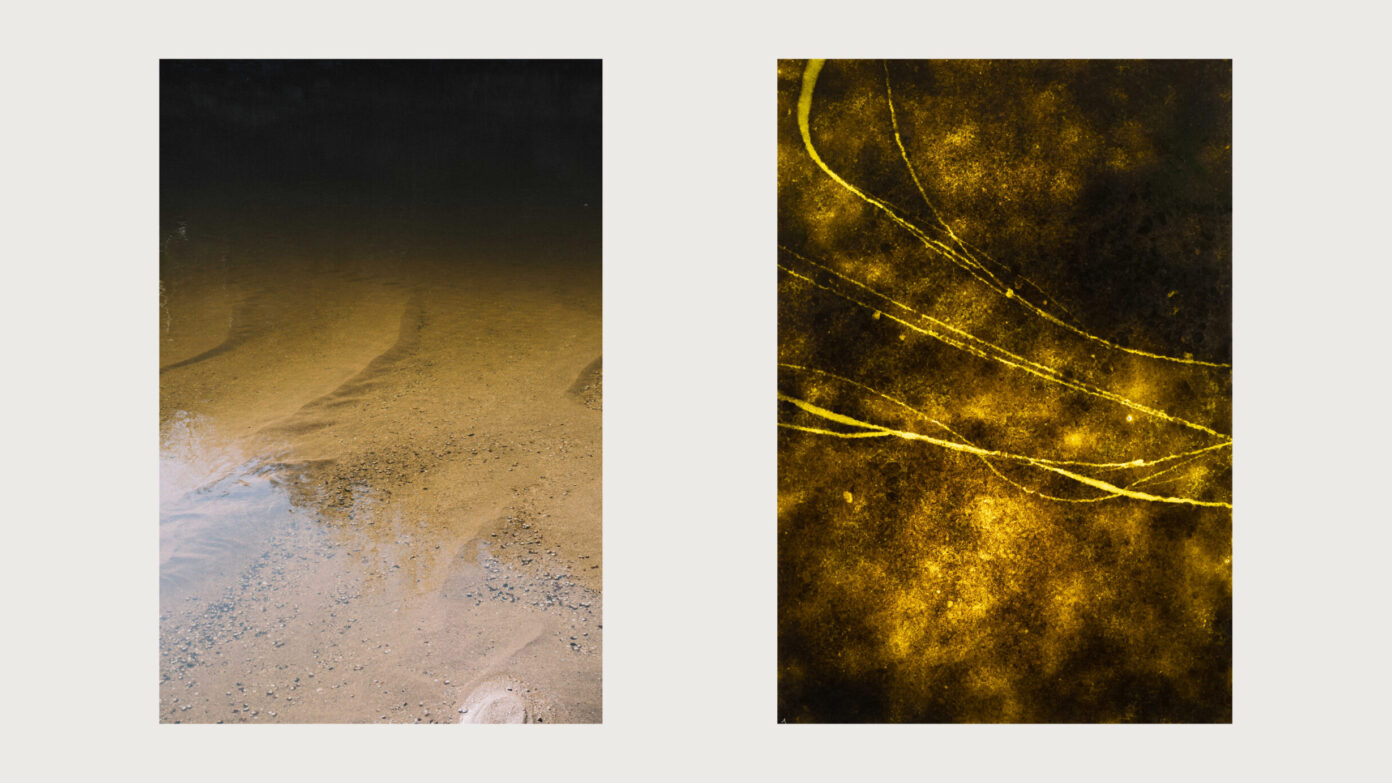

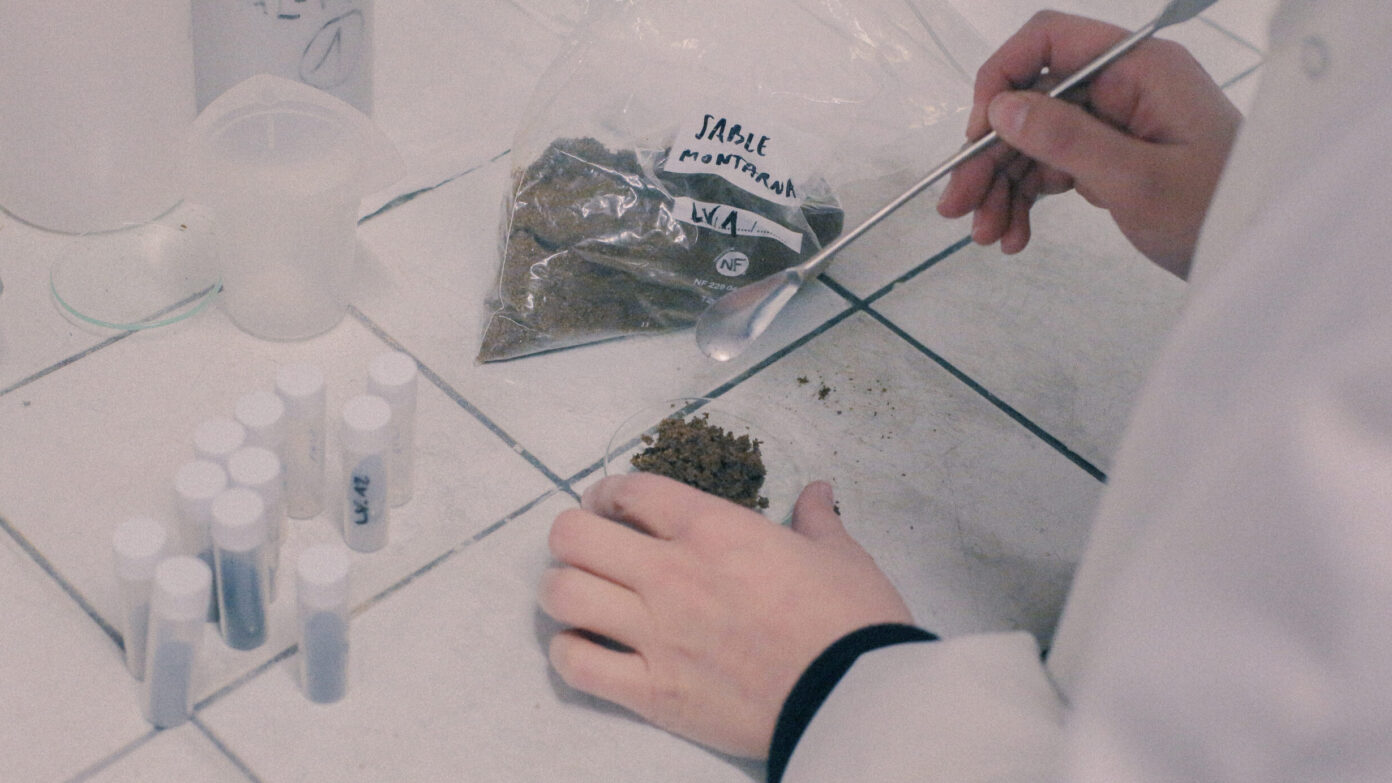

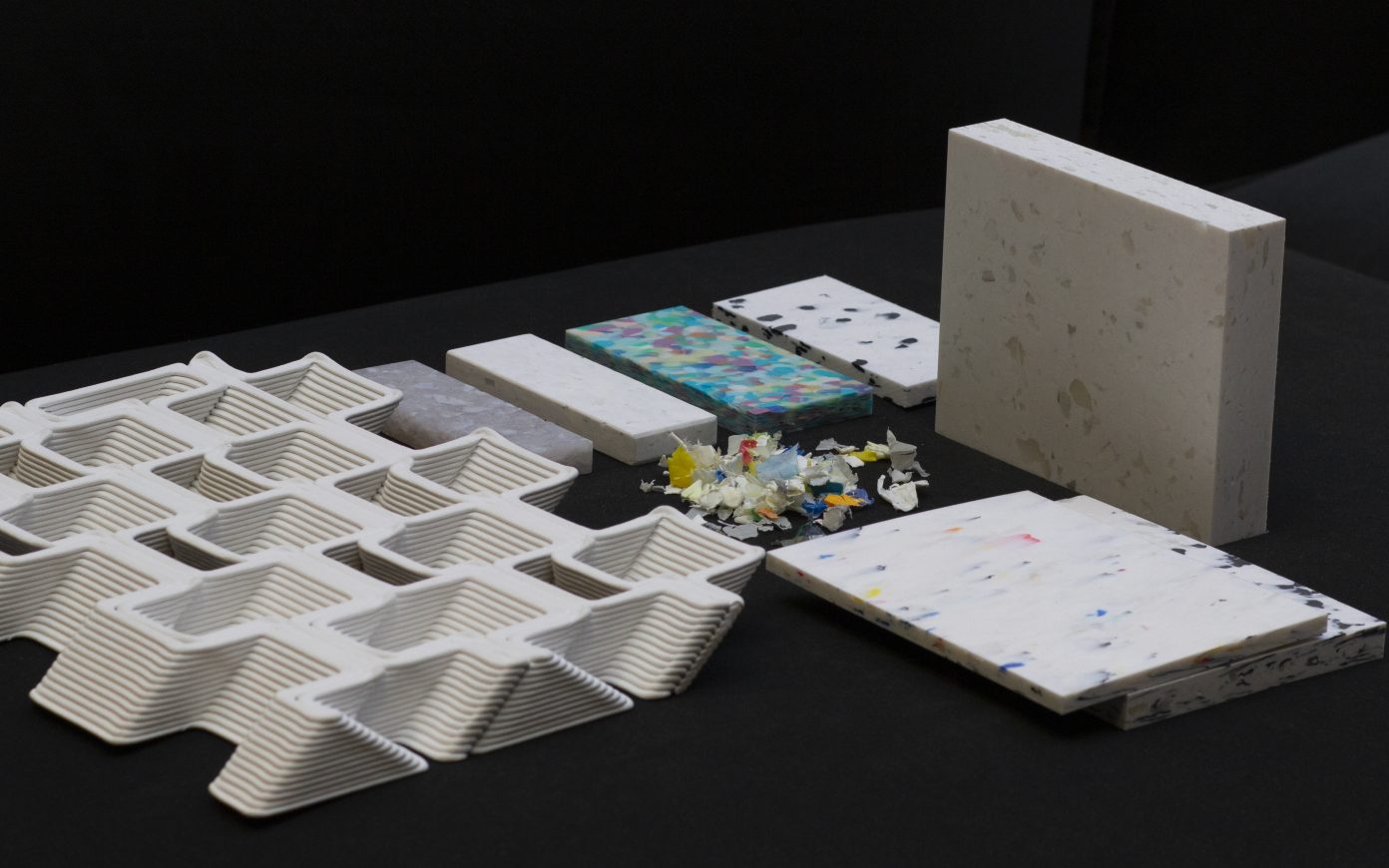

Geoglasswork (géoverrerie) is a term we recently coined to describe an approach that aims to bring together geography and the base materials that are used to manufacture glass. The qualities and properties of glass vary depending on the base inputs that are combined—chemical feedstock, sands from all across the world, oxides, et cetera. In my case, glass—its color and its behavior under high-temperature conditions—varies based on which materials I use. I work with materials that are seldom used, including powdered seaweed, and oyster, abalone, and snail shells, as well as microalgae, and sands sourced from the construction industry. The glass items I make vary depending on the nature of these materials. They are based on the landscapes they originate from, their geologies, their traditional productions (some of which are now perceived to lack value and characterized as debris), and the know-how that have generated them.

The most significant factor in allowing the materials used in glass production to express themselves relates to working on color and revisiting primitive production techniques. The history of glass has always been about pursuing a quest for purity and transparency. The search for colorlessness and the desire to reconstruct rock crystal has pushed glass producers to continually discolor glass, which naturally has yellow or green hues. Today, we end up with something I feel is incoherent, whereby we first discolor glass before imbuing it with color at a later stage in order to keep the tints under tight control. We have thus lost the richness of geography and the expression of the trace elements that are naturally present in the base materials and which body tint the glass with deep colors.

Geoglasswork, the color and volumes, and the glassware that is ultimately produced become archival elements of a territory, a pretense to relate its history, its heritage, and its know-how.

What sort of relationships do you have with scientists and research labs, being at the crossroads of art and science as you are?

Beyond creating objects or projects of a more architectural nature, my work consists in establishing an ecosystem of researchers, artists, and craftspeople, and to assert my place at the junction between art and science. It can sometimes be difficult to gain recognition of either party and to have each embrace cross-disciplinarity as the only solution to break free from knowledge silos in order to produce in a consistent manner while respecting the localism, fostering the process of reclaiming of materials, and the understanding of ecosystems.

As for my forays in the chemistry of glass, they are informed by the residence that I have been fortunate to pursue since 2017 at the Glasses & Ceramics Laboratory at the Rennes Institute of Chemical Sciences. I am also interested in marine biology and am working, among others, in collaboration with Vona Méléder, a researcher at the University of Nantes and a diatom specialist. Diatoms are a group of microalgae that generate around 25% of the oxygen produced on Earth every year. The pressing challenge in terms of raising awareness and communication around microalgae has led us (working in tandem with master glassmaker Stéphane Rivoal) to make sculptures that are intended to assist in science outreach. The work is a technical and esthetic challenge as we must respect the specific characteristics of each species, while seeking to arouse a sense of wonder in order to educate the public on the importance of preserving this precious resource. Each year, we create a sculpture based on a diatom chosen together with the researchers. We’re currently collaborating with Jean-Luc Mouget from the University of Le Mans to reproduce Haslea ostrearia, a species that should be familiar to all given that they are behind the color of the green-gilled oysters from Marennes-Oléron!