The Paris Design Week, Trend Barometer: Yes to Recycling, But What About Repairing?

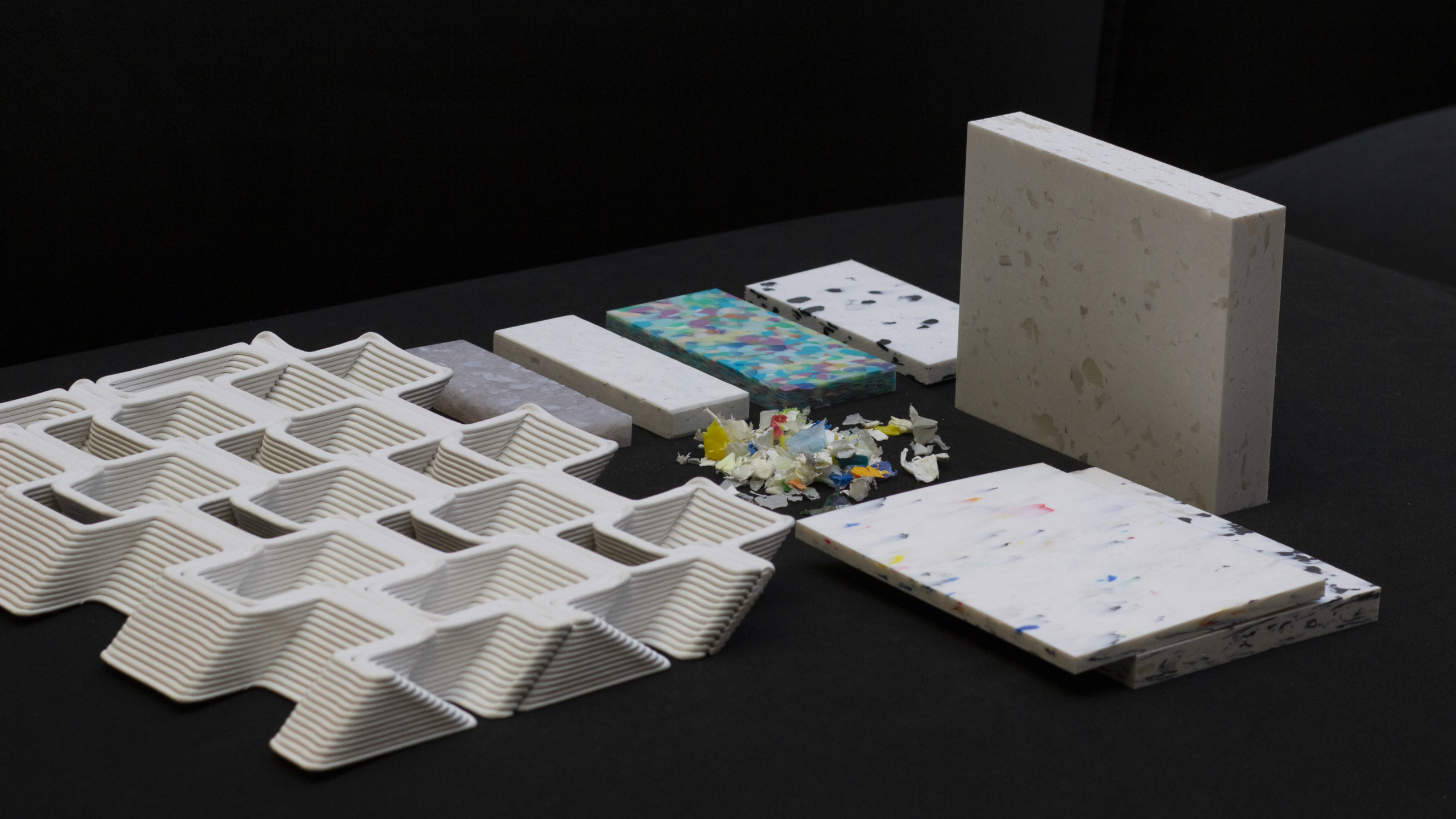

The Paris Design Week took place from September 8 to 17, 2022. Recycling appeared as a recurring theme, mostly based around plasticThis concerns both PIR (post-industrial recycled) plastic, which is the raw material made from waste generated in the industry, and PCR (post-consumer recycled) plastic, as is the case with Le Pavé®’s products for instance.. This week presented the opportunity of observing the growing commitment on behalf of design houses in favor of environmental considerations, with the likes of Kartell, Muuto, and Vitra presenting environmentally responsible lines of furniture often consisting in the reissue of one of their existing lines made from a recycled material.

Yet the merits of these objects, though made from recycled content, raise questions. Wouldn’t a chair made from single-use coffee capsules serve to justify generating this waste product in the first place if the responsibility for recycling the plastic is then transferred to the furniture manufacturer as a result? Design houses give little thought to the waste they recover and the production models that they complete. Even though the lines of furniture made from recycled plastic are theoretically recyclable, few brands offer to take back the product at the end of their service lifeCertain brands offer to assume responsibility for the end of the life of their products, as is the case of Komut (with its line of furniture in recycled plastic manufactured using a 3D printer) and Really (a branch of Kvadrat that offers a range of products made from recycled textile fibers), which have both committed to end-of-life product take-back to recycle them., revealing a lack of commitment over the long run. But the lack of interest in the future of these objects doesn’t stop at the end of their use and concerns their entire service life. Indeed, the manufacturer’s responsibility often stops at the very moment an item is unboxed, with no service being offered for repair or spare parts. However, the attention paid to fragility is deployed in a material ecology and shapes the awareness of the value of thingsCare ethics, together with consideration for things and objects—repair and maintenance—provide a new source of insights for guiding urban design. Maintenance and repair studies are thus a promising field in the sociology of technology. They look into the practices, trades, knowledge and devices that contribute together to ensure the durability of all that surrounds us. In France, Jérôme Denis and David Pontille are developing a research program on urban maintenance activities at the Centre de Sociologie de l’Innovation des Mines.. This implies that items can be repaired and that they are designed and produced in a way that makes this possible, both in the selection of the materials they use and in the assembly of their partsFor instance, Tiptoe designs furniture for disassembly, so that any part can be replaced independently from the rest and so that each material (including the recycled plastic) and be conveniently reused or recycled..

Due to its poor image, plastic therefore emerged as the first material that instigated thinking about recycling for many brands. As recycling leaves only imperceptible traces, it allows design houses to stick to a conventional aesthetic, design process, and production chain. However, the recycling of plastic isn’t truly frugal as long as the transformation process doesn’t extricate itself from the logic of newness and the idea of perfection. Beyond materials, a paradigm shift in furniture design is needed, stemming from consideration of the entire production chain, from raw material supply to its transformation, transport, assembly, maintenance, renovation, and all the way through their end of life and the supposedly infinite “closed-loop” recycling of the material.

Laélia Vaulot, Environmental Strategy Manager at PCA-STREAM