The increasing density and progressive mix of social classes during the 1950s and 1960s resulted in the exodus of the wealthy population. They began to flee this melting pot that had become dense and noisy for Leblon and Ipanema, the new districts next to Copacabana that were still relatively underdeveloped and that were based on a more elitist model, as well as on a smaller scale. Copacabana entered into a phase of progressive decline, due mainly to the aging population, as the urban dynamics of the time led the young and affluent to move westward to the new suburb of Barra da Tijuca that began to be develop in the 1970s. Their grandparents remained and new residents occupied apartments that had become cheaper, while the public authority abandoned the old postcard image of the city, and Copacabana deteriorated, informalized, and the area became unsafe.

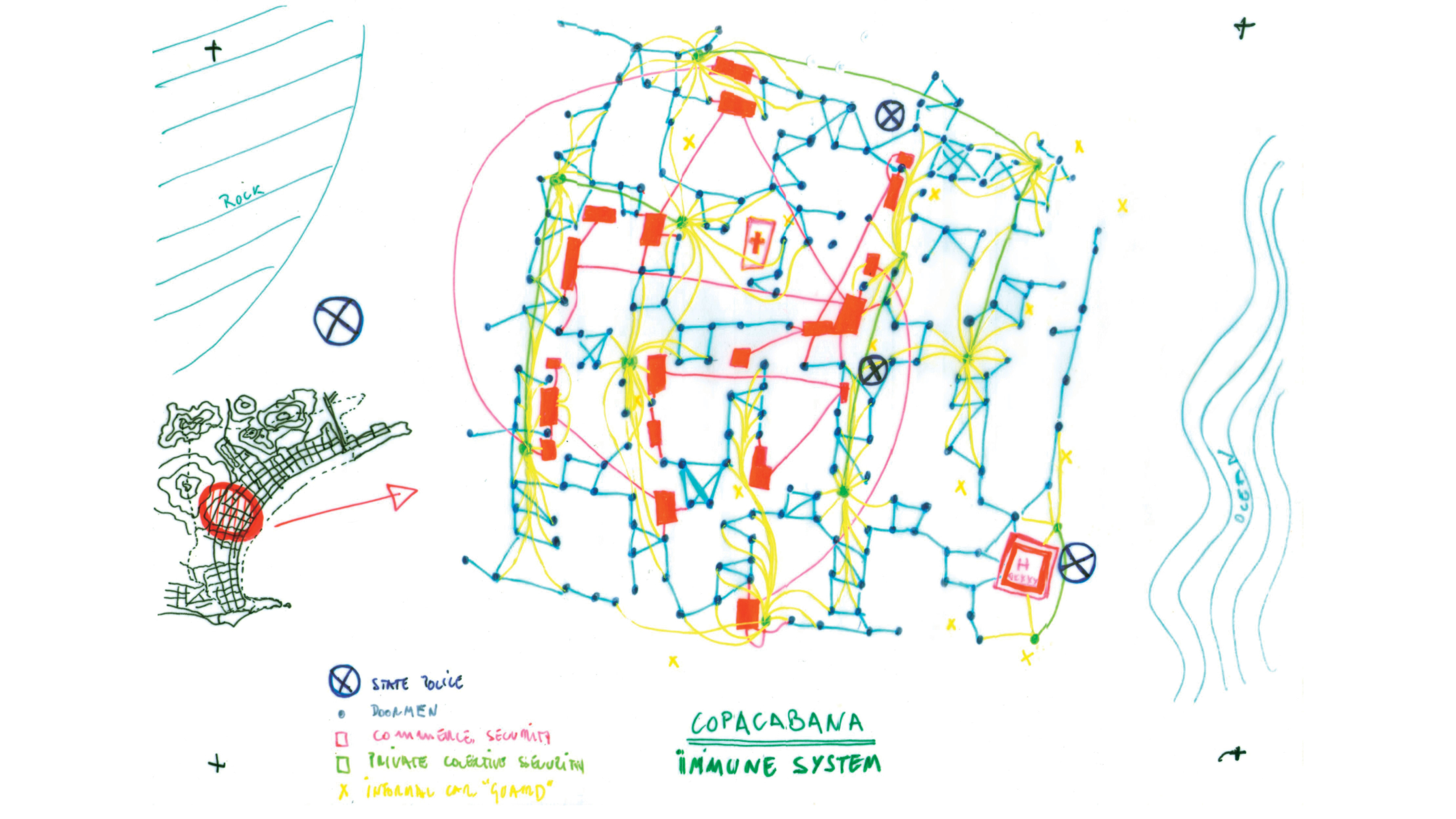

And yet the area resisted, continued to function, adapted, and the different agents in the complex universe that now constituted its people and its economy, created in a symbiotic way different levels of cohabitation. Due to the virtual absence of a regulator or local authority, various mechanisms were developed and put in place to compensate for the lack of a central authority to organize urban life. The relationship to the beach and its seaside town dimension was also one of the factors that saved Copacabana from disaster.

New limits were reinvented over time and rules of cohabitation became unspoken yet generalized norms. New roles were created along with new functions. The new Copacabana would inherit from its heyday the role of the doorman, who controlled the entrance to a building, but who also formed a communication and security network that spread throughout the neighborhood.

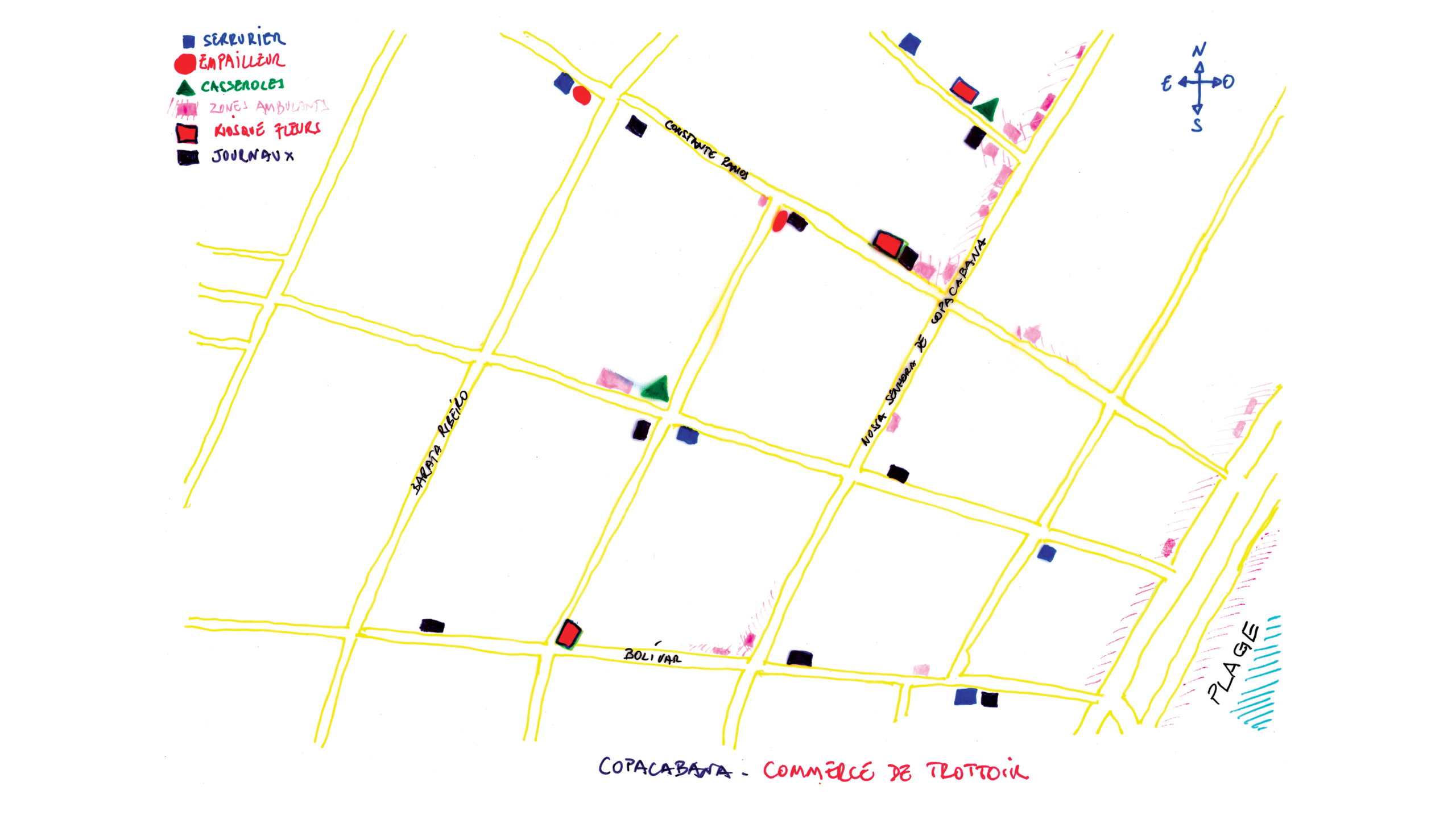

Public spaces, and in particular streets, were reorganized and used in a way never imagined by the modern planners of this vertical neighborhood.

Since the 2000s, Copacabana has had a rebirth. The extraordinary survival of the “Copacabana” image and a return of a younger population, coupled with the prosperity gained throughout the decade has seen the transformation of the dense population into a major asset, one that has generated revenue for the government. Despite this, the alternative systems that were developed over time are still in place and coexist with the institutional systems. The area became a meeting point for the whole city, where all social groups are represented, and people come from everywhere to eat, go to the dentist, work, go to the beach, walk, go out, and beg. Copacabana has become the tourist heart of the city of Rio, its picture postcard. The public authorities have once again begun to invest in the neighborhood, organizing many events for large crowds, often improvised somewhat precariously, bringing two million people to the beaches of Copacabana.

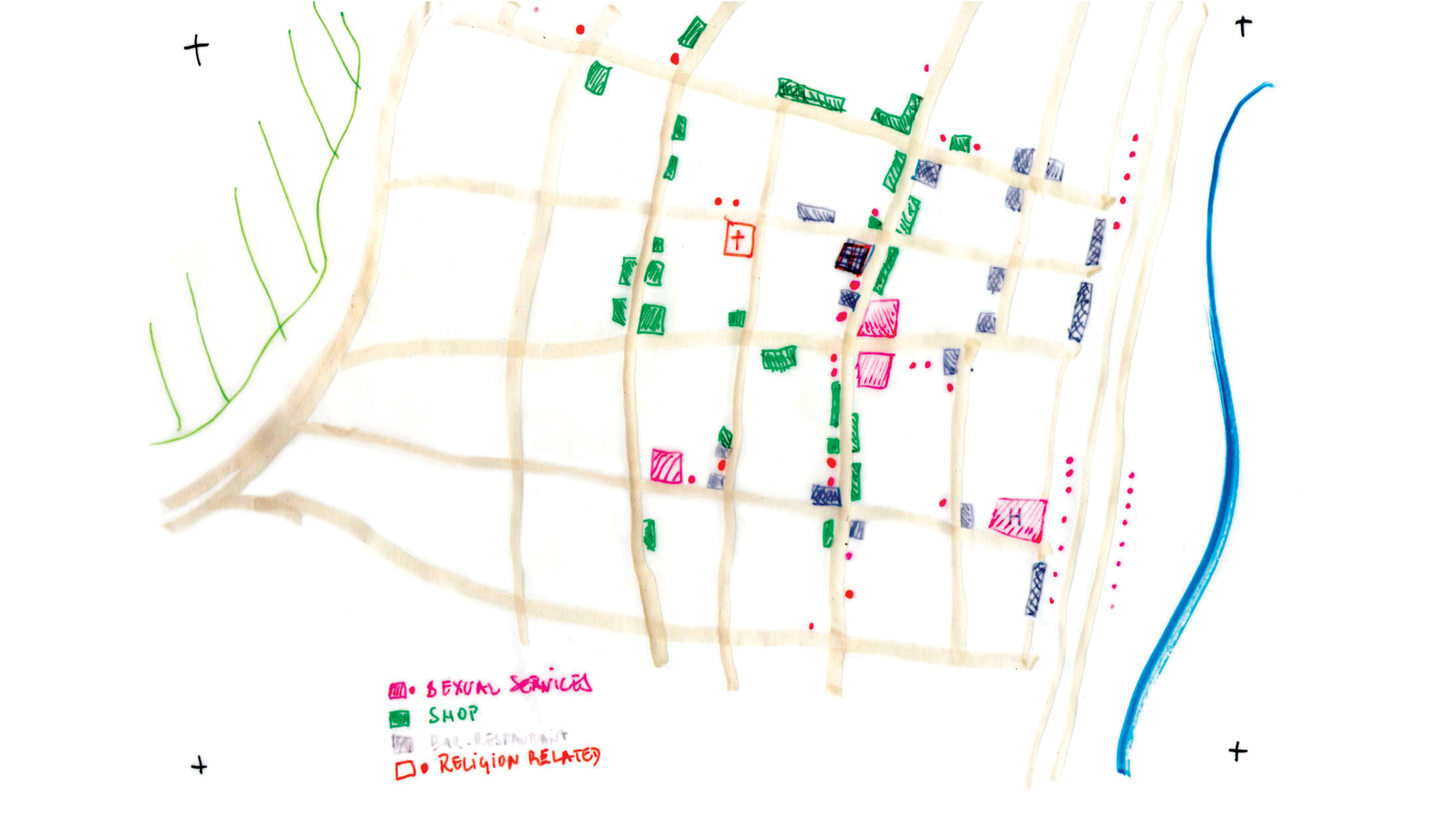

The period of abandonment of Copacabana allowed for a seemingly chaotic organic growth, but in reality it was very structured. A responsiveness to freedom and a laissez-faire attitude took hold between the rocks and the sea, between the canyons of the buildings, in the recesses created by endless interventions in the urban fabric, and even within buildings. This process of organic and unplanned reorganization (the original unprecedented growth and the abandonment that followed) has produced much of what Rem Koolhaas defined as “junkspace.” One can find in the same building dentists, realtors, manicurists, electronics stores, sexual services, boutiques, religious temples, a pharmacy, and sometimes even a bank on the ground floor.

The emergence of three favelas surrounding Copacabana has also made available an inexpensive labor force that lives nearby, allowing the establishment of a large network of low-cost services that are a feature of the area, especially for the 25 percent of the population who are retirees living there and who are in need of countless services.

This is the diversity that makes Copacabana so interesting and which has created a context of freedom. It extends to the relationship between the outside and the inside, because, from the outset, the buildings had entrances that were a continuation of the street, without clear boundaries between public and private space. During the period of elevated crime rates, between 1980 and 2000, almost all buildings were equipped with gates separating them completely from the street. And yet, despite this physical barrier, the inside/outside relationship retained its permeability.

Many temples of worship of various beliefs, and their corresponding supply stores are also part of the context of the city neighborhood: there are Catholic churches, synagogues, Protestant temples of various persuasions, spiritualism centers, places of worship for Afro-Brazilian religions, Umbanda, Candomblé, and Quimbanda, and oriental religions. It is not uncommon to see voodoo offerings at intersections along with chickens roasting, candles, and cassava flour in earthen pots.

Copacabana is also a hotbed of sexual services, with a huge concentration throughout the neighborhood of brothels and street prostitution. A “secret” relationship between hotels and the sex economy has created an underground services network for tourists. It is a significant but ignored part of society that is not regulated and has spread throughout the area of Copacabana to mix with other branches of the local economy and its general activities.

The vast majority of Copacabana’s streets are culs-de-sac which abut on the rocks or terminate at the seafront. This is a characteristic of Copacabana and there is only a limited number of thoroughfares by tunnel or along the coast, creating a kind of insularity that promotes a community spirit and the development of a certain self-sufficiency.

Urban microcosm

Copacabana is now a city-neighborhood or city-district containing everything a city can offer, though on its own scale. There is even a “nature reserve.” With its estimated population of between 150,000 and 200,000 inhabitants, to which one can add over 10,000 tourists staying in hotels and other accommodation, Copacabana can provide everything that an individual needs from the moment of their birth in one of its hospitals. They may attend one of the many schools in the area, then go to college or take a technical course, work in one of the countless companies located in Copacabana, enjoy their retirement at the beach before taking advantage of funeral services where residents are buried in the cemetery on the other side of the tunnel, in the adjoining district of Botafogo.

At this very moment Copacabana continues to evolve, driven by the recent prosperity of the country and of the city itself, which has caused a sharp increase in the value of real estate, but also because of generational renewal due to the gradual departure of older residents. How will these organic systems, which were created over decades, change in the face of this new situation? What other systems will evolve? The answers remain as elusive as ever. Somewhere between the Generic City of Rem Koolhaas and its antithesis, Copacabana continues to exist in a dynamic and unpredictable complexity, linked to the specifics of the territory, a unique environment and one that has been relatively unaffected by globalization.