Luxury and Chapels in Tokyo

- Publish On 11 January 2017

- Taro Igarashi

The construction of remarkable architectural objects for international big luxury brands has accelerated the past few years in the Land of the Rising Sun. The emergence of purely commercial and non-religious wedding chapels has become a Japanese idiosyncrasy. These two trends reflect two different approaches of global contemporary architecture. The quality of experimental research in luxury flagship stores contrasts with the dreadful pastiche of the Gothic style of the weddings chapels for various reasons that will be explored here.

Born in 1967, Taro Igarashi holds a PhD in engineering. He is an historian and architecture critic. He teaches at the University of Tohoku in Sendai, Japan.

The Urban Development of the City of Tokyo after the Burst of the Economic Bubble

Toto Editions published two guides that experienced strong sales that were quite exceptional for this type of work. The first one, Kenchiku Map Tōkyō—The Architectural Map of Tokyo (1994) has become the reference book on the architectural heritage of the Japanese capital of the period of the economic bubble. It highlights the considerable influence that postmodernism, which was then booming in Japan, has exerted on the architects of the archipelago and lists the numerous works of great variety, both in terms of forms and color, that is has brought about.

The second guide, Kenchiku Map Tōkyō—The Architectural Map of Tokyo, Part 2 (2003). In it, I compiled a comprehensive list of buildings, allowing me to see that, even after the burst of the bubble economy, Tokyo remained a monstrous city where new constructions proliferated. Of course, there have also been changes. For example, the number of average-sized public institutions has decreased while renovation works have mushroomed. Some districts, among other Roppongi Hills and Shiodome Shiosite, have gone through major redevelopments while individual houses proliferated, such as the Mini House by Atelier Bow-Wow or Kazuyo Sejima’s Small Houses. In other words, Japanese architecture evolved in two opposite directions, due to the rejection of urban sprawl on the one hand and a return to the city center on the other hand.

The urban development of the city of Tokyo nevertheless seems quite modest in comparison with what is happening in China. The buildings that emerge from the ground in Beijing or Shanghai have impressive proportions in terms not only of height but also of width. In China, there is no private land tenure, which makes it possible to entirely restructure a neighborhood just as if it were an uninhabited site. In Japan, however, land fetches a very high price and is fragmented into small plots due to the traditional tenure system of inheritance, which has led to a proliferation of completely vertical buildings (the so-called “pencil buildings”). In addition, in Tokyo, large-scale urban development has remained relatively restrained and measured, completely unlike what is happening in China with bold architects such as Rem Koolhaas and Riken Yamamoto. From a global perspective, the small dwellings of Tokyo display greater originality than other architectural forms. In Europe and the United States, houses are larger and people who do not own one live in apartments. But among the Japanese, there is a strong desire to own land and a home, however small. Lately, the renewed interest in city centers has been compounded by the purchase of small urban housing at the expense of large suburban houses. In the rest of Asia, most people live in apartments, just as in Europe and the United States, even if part of the well-off live in sumptuous residences. But in Tokyo, small dwellings constitute a distinctive architectural form. Two opposing architectural trends have emerged in Japan after the burst of the economic bubble. Two types of buildings have become extremely fashionable and they are neither gigantic urban developments nor individual houses but the flagship stores of major brands, designed by famous architects, and wedding chapels. In both cases, these are commercial spaces that target a female clientele.

Major brands and wedding ceremonies play an important role throughout the world but, in Japan, they are experiencing a particularly remarkable expansion. According to a survey conducted in 2003, 44% of Japanese women aged 15 to 59 own a Louis Vuitton-branded bag. One third of the global sales of the Maison Louis Vuitton can be traced back to the Japanese clientele. The phenomenal success of this luxury brand in Japan is due to a willingness of women not to assert their own identity but to play it down and ensure that they all look alike. Curiously, Japanese schoolgirls carry both high-end branded purses and trinkets purchased in low-priced stores, a form of inconsistency that is readily admitted in the archipelago. In addition, more than 60% of couples want their marriage to be celebrated in a church even though barely 1% of the Japanese population is in fact Christian.

At the same time, Christmas Eve has become a celebration of romance. In order to respond to demand, “cathedrals” dedicated to weddings and where no congregation gathers to pray have emerged in all the provinces of the archipelago—this type of activity has become an industry. Japan is the only country in the world where the Catholic Church authorizes the celebration in churches of marriages between non-believers.

An Architecture that is Comparable to those of the Pavilions of the Universal Exhibitions

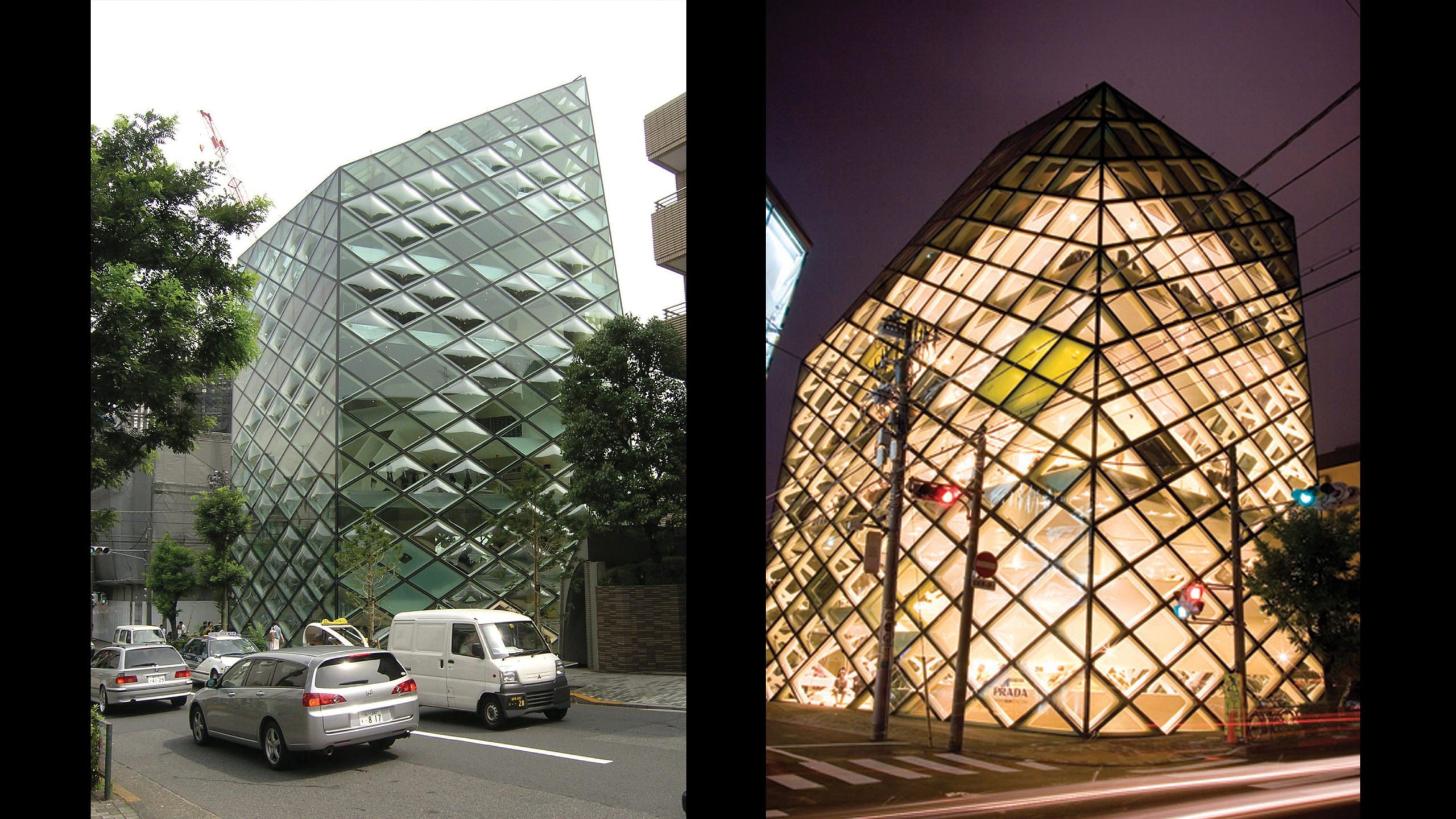

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, Tokyo has seen a succession of gigantic architectural projects; in terms of architectural quality, what happened in the districts of Ginza and Omotesando is particularly worthy of interest. Entire buildings are being designed as flagship stores for major luxury brands. These new retail outlets are in fact genuine experimental attempts, unlike the ordinary large building projects. For instance, when Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron designed the Prada flagship store in Aoyama district in 2003, they gave the building a truly remarkable futuristic diamond-shaped shape. They designed the building with the greatest care in contrast to numerous other foreign architects who have often only perceived façades of large buildings as prestigious promotional displays for their own name. But the Prada flagship store is a work of a new type, including in terms of the architecture itself. Far from merely curtain-walling a façade without taking into account the structure of the building itself, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron have given the Prada store the bold appearance of a giant crystal with a diamond-shaped concrete grid filled with different types of glass panels.

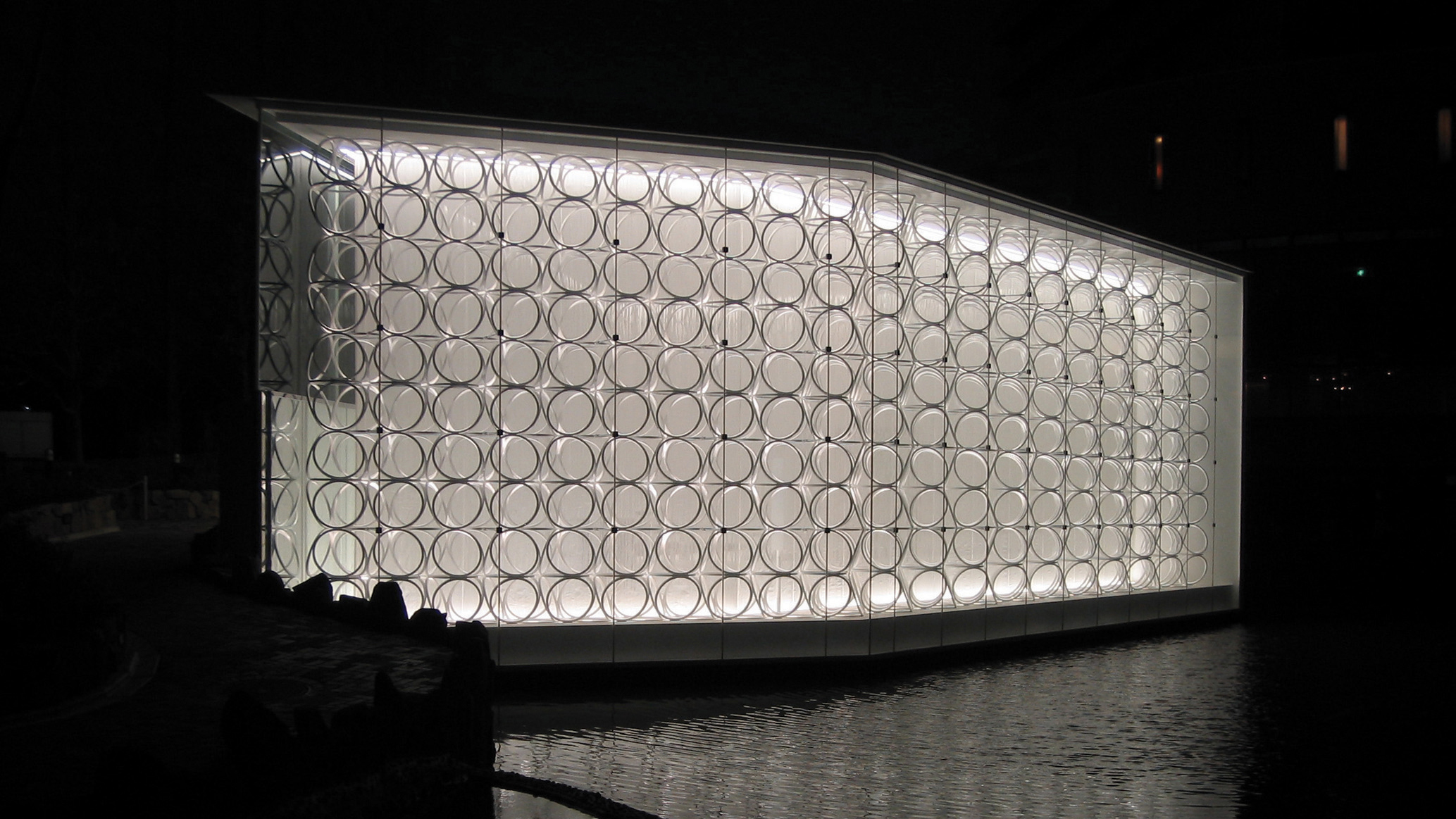

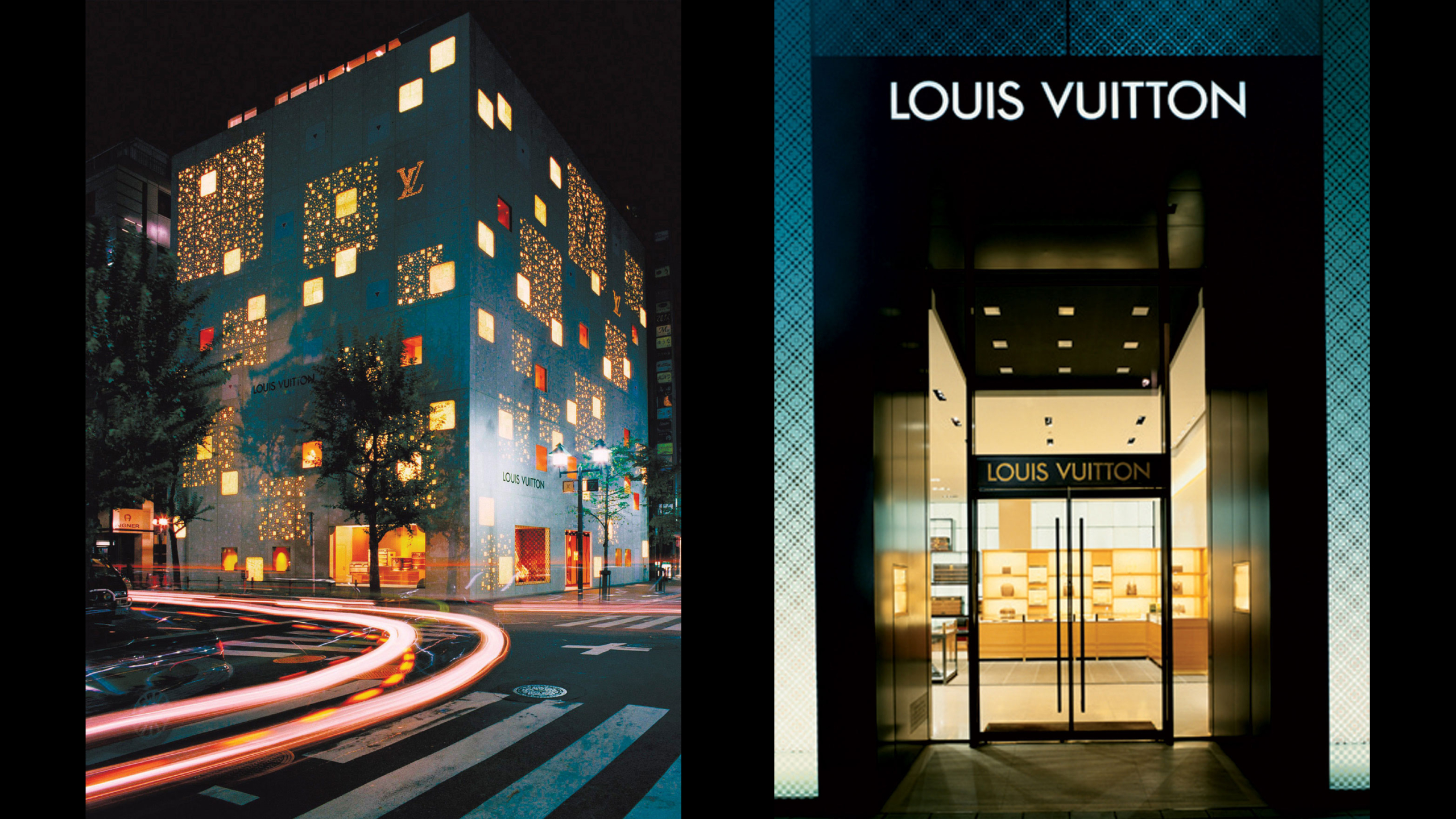

The alignments of fashion stores in the streets that go from Omotesando to Aoyama have completely changed. New buildings by eminent contemporary Japanese architects have been erected in this district where Kenzo Tange had already built the Hanae Mori building in 1978 and Tadao Ando the housing units of the Collezione. Lately, there has been a real flowering of architectural works, among others the Louis Vuitton flagship store in Omotesando, produced in 2002 by Aoki Jun, the One Omotesando building by Kengo Kuma, with its series of vertical wooden fins placed perpendicular to the façade (2003), and the Christian Dior Omotesando flagship store designed by the architecture firm SANAA (Sejima and Nishizawa and Associates) and whose second inside skin of translucent acrylic panels evoke the drapery movements of fabric (2003). In 2006, the architectural complex of Omotesando Hills by Tadao Ando became the latest of a series of decisive productions. As for the design of the Tod’s building in Omotesando (2004), which houses a huge store dedicated to the famous Italian footwear retailer, it was entrusted to Toyo Ito. After having built the masterpiece that is the Sendai Mediatheque (2001), Toyo Ito, far from resting on its laurels, has pushed his research even further and is making new attempts. Tod’s flagship store mimics the shapes of the elm trees (keyaki) that are planted along Omotesando Avenue. Toyo Ito used the trees not only as a graphical pattern, but to define the crisscrossing geometric forms of the structural concrete façade, blended in with clear glass that fills the gaps. In doing so, he has managed to find an experimental form that integrates structure and form, or in other words, the abstract and the concrete, in an organic way.

In 2005, Toyo Ito produced the Mikimoto building in Ginza, through which, in the manner of a contemporary Gaudí, he has given a new definition of the relationship between structure and ornamentation. When one walks all the way down to district of Ura Harajuku, one discovers the works of the new generation, that of Hitoshi Abe and Takaharu and Yui Tezuka. These architects, that are far from carefully planning everything in advance, explore new paths and their remarkable work is in the process of leading to a new form of architecture. Starting at the end of the 1990s, all major luxury brands commissioned architects to build flagship stores. Rem Koolhaas got to work on several projects in the United States, but it is mainly in Japan that the commissions were the most numerous. In the store that they were asked to create, each architect deployed in a remarkable manner their individual sensibility vis-à-vis the materials and the external appearance of the buildings.

Since the very beginnings, architecture and garments have always shared the common feature of wrapping up and protecting the human body. In their design, the prestigious architects working on flagship stores have often evoked the theme of skin and clothing. In these purely commercial buildings, the important point is the aspect of the façade. Encouraged by the enthusiasm of their clients, the architects are no longer limited to a simple drawing of the façade walls, which gives rise to all sorts of innovations in terms of design. This phenomenon is quite interesting if we compare it to what happened around 1990, when the Disney company commissioned architects of the post-modern school such as Robert Venturi, Michael Serious, and Arata Isozaki, to build facilities, notably its headquarters. Of course, there is no lack of people to criticize the exceedingly narrow links between architects and the world of capital. As for myself, I do not see anything bad about this as long as this forms a way of encouraging the expression of the trends of the avant-garde. All the more so given that in Japan today, architects have increasingly less opportunities to take part in projects for public or state institutions. To such an extent that Tadao Ando and Toyo Ito are looking for orders abroad. SANAA (Sejima and Nishizawa and Associates) was founded in Tokyo in 1995 by Kazuyo Sejima and Ryūe Nishizawa, but although these architects desire to work more in their own country, a full eighty percent of their work is taking place overseas.

Flagship store architecture seems to be similar in nature to that of the pavilions of the world’s fairs. These two forms of architecture share the common features of not being intended to last forever and forming an attempt to implement a bold design. The world’s fairs of the nineteenth century have presented genuinely innovative constructions, notably the Crystal Palace of the London’s Great Exhibition of 1851 and the Eiffel Tower of the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris. But Expo 2005, which has held in Aichi, highlighted a return to traditional and conservative architecture, which is why flagship stores currently hold the pioneering role in the field of architecture.

Today, the fashionable streets of the districts of Omotesando and Ginza serve as a showcase of avant-garde architecture. At the time where Kenzo Tange (1913‒2005) occupied a prominent place in formal national architecture, Kunio Maekawa (1905‒86) in provincial administration office architecture, and Arata Isozaki in that of museums, the construction of buildings for commercial use was not held in high esteem. Now, in this early twenty-first century, the experimental design of flagship stores has become the most highly regarded form of architecture, which is completely unprecedented in the history of architecture.

Architecture in the Context of the Media

As clients, major brands stimulate the creativity of architects, and, at the same time, experimental architecture improves the image of luxury brands. This dynamic relationship between fashion and architecture started in 1999 with the Louis Vuitton store that was so perfectly designed and developed by Aoki Jun in Nagoya. When we look at the history of Louis Vuitton, we find that it was the first time that the major handbag retailer had opened a standalone boutique opening on the street in Japan. Before the repeal in 1979 of the Law on Foreign Capital and the abolition of the Foreign Capital Commission, the establishment of foreign-capital companies in Japan was strictly limited.

Big brand boutiques had to use the retail network of the local department stores to be able to sell their products in the country. Hermès would sell its products in department stores via a representation contract, while Loewe leveraged stock ownership in a Japanese wholesaler that specifically supplied with department stores. This explains why the ground floor of department stores was often occupied by alignments of booths of major brands. But, starting in 1990, capital-control measures were relaxed even more and major brands started having shops outside of the large department stores and in standalone premises with a street-side storefront. Furthermore, cracks began to show in the age-old trading model of the department store and some of main department stores foundered. The fate of major brands was now no longer linked to that of the department stores. The new look that the architect Aoki Jun gave in 2004 to the Louis Vuitton store on Namikidori Street in Ginza is quite symbolic of the fact that department stores were losing steam. Whereas the store designed in 1981 by the department store Sogo was a composite one, the 2004 store was entirely dedicated to Louis Vuitton and Aoki Jun endowed it with a new façade that gives it the appearance of a gift package.

In Japan, the luxury industry is doing wonderfully in spite of the recession. The turnover of Louis Vuitton Japan is steadily increasing and amounted to 117.9 billion yen (circa 786 million euros) in 2001, 135.7 billion yen (940 million euros) in 2002, and 152.9 billion yen (1,093 million euros) in 2003. In 1999, Japan took over France as the main geographic market of Hermès for the first time since the company was founded. Kyojiro Hata, the President of the Japanese branch of Louis Vuitton, declared: “After seeing the Louis Vuitton store in Paris, I became convinced that to get our customers to understand the true values of the brand, it was absolutely necessary to convey its unique history, traditions, techniques, and aesthetic consciousness. I also became convinced that the store was the ideal place where this was to be done.

If we do not place the products in their exact traditional and historical context, there is a high risk that we will eventually end up ‘making an image of the Buddha without giving it a soul,’ as the Japanese proverb goes, and thus failing to convey the dream that is embodied in the brand and that is in fact its true value”. The idea of using the shops as an advertising medium is nothing new. The image of the big luxury brands is not adapted to the mass media such as television or the press. Due to the recession, high-interest money-lending (called sarakin) are prevalent in television advertising in Japan. As for the press, ads for major brands undoubtedly suffer from promiscuity with the articles that fill the columns of the weekly magazines. Compared to the cost of advertising in the mass media, where costs often amount to tens to hundreds of millions of yen, building construction costs do not appear that high.

On the other hand, with such sums, architects can consider launching true adventures. In Japan, flagship stores have now become places of pilgrimage. Indeed, luxury flagship stores are sorts of monuments that are intended for promotional purposes. The Japanese who visit the luxury stores of Ginza and Omotesando believe that the prices there are high and they try to do their shopping abroad. It is therefore right to say that the shops of the major brands of Japan serve as showcases for faraway countries. In the context of the linkages between architecture and fashion, it should probably also be mentioned that architecture is currently experiencing a prodigious craze in Japanese magazines.

In 2000, in particular, the fact that “Casa Brutus” had become a monthly magazine has played an emblematic role in this regard. Taking the theme of the journey, the magazine presented designer hotels in every region of Japan as well as the most recent achievements of very famous architects, among others Franck Gehry. “Casa Brutus welcomes architects as if they were great chefs.” This magazine also includes many pictures of fashion models posing next to recent buildings and publishes articles that deal with both fashion and architecture. Major luxury brands are major advertisers in these publications. The editor-in-chief of Casa Brutus also pointed out that now that clothing and food are no longer as prominent in their lives, the Japanese are becoming more interested in housing. His goal is to make the name of the architect Le Corbusier as famous as that of a major luxury brand. The fact that famous architects have designed many of these flagship stores certainly contributes to the image of luxury products. Of course, critics will point out that mass-audience magazines treat the subject of architecture as nothing more than a consumption good, unlike the specialized journals that architects read.

The “Wedding Chapels” Craze

Starting in the 1990s, Japanese wedding magazines such as Zexy, Kekkonpia, and Lei Wedding began to appear on the Japanese market. They were targeted at a female audience and when we look closely, they present themselves in the form of magnificent catalogs of wedding chapels and wedding dresses. Parents or intermediaries used to select the places where Japanese couples celebrated their weddings but as soon as specialized magazines were starting to be published on the subject, couples seem to have preferred to choose for themselves. It explains why the design of the churches has become so lavish.

According to a 2005 survey conducted by the magazine Zexy, the average amount that Japanese newly-weds spent on their wedding ceremony and reception amounted to 3.38 million yen (22,500 euros). The churches were designed to serve as a grandiose scenic device for these outrageously expensive celebrations. Formerly, eighty percent of the Japanese married following the Shinto rite, but today, only fifteen percent do so, while the number of marriages celebrated in the churches exceeds sixty percent.

Given that churches are intrinsically buildings that accommodate a congregation, wedding chapels cannot be considered religious buildings. But this situation is highly revealing of the way the Japanese understand religion. The wedding chapels of Las Vegas may have foreshadowed what has happened in Japan. Everyone knows that weddings that are celebrated in such a context reek of fast food with paperwork that is simplified to the extreme. There are even drive-thru wedding ceremonies that allow future spouses to exchange their consent without leaving their car.

The presence in the United States of a place as exceptional as Las Vegas is explained by the influence of the Christian religion in this country. In Japan, there are wedding chapels in all regions although the role played by this religion is very low. What is more, these buildings are used for lavish and exceedingly expensive ceremonies, contrary to what most often happens in Las Vegas. It is said that there are around six hundred wedding chapels in Japan. The largest number of them is located on hotel grounds or in ceremonial centers and was built in the past ten years. The architects Tadao Ando and Aoki Jun, who have designed flagship stores, have also built “wedding chapels,” namely the Church of the Wind, also called the Chapel on Mount Rokko, in Kobe, and the Church on the Water for the former, and White Chapel, in Osaka, for the latter. They have not conceived them as religious buildings but as places to celebrate weddings. The Church of Light, which was built by Tadao Ando in Asuka, is somewhat an exception to the extent that it is an actual church, though it shows only minute design differences from his wedding chapels.

The vast majority of wedding chapels were built in the style of European churches and the Japanese particularly appreciate the Gothic style which, for them, is strongly linked to the image that they have of churches. Aïchi Prefecture thus has Saint-Tour Cathedral, which was modeled on Notre-Dame de Paris, and Saint-Patrice Cathedral, which is a replica of the Cologne Cathedral. Remarkably, the stairs of this type of building tend to be huge. The reason for this is probably that staircases provide an ideal setting to highlight long-tail wedding dresses, the theatrical staging of confetti of flower petals, the wedding bouquet, and wedding photography to commemorate the event.

In any case, there is no evidence that the number of Christians is increasing as a result. The latest fashion in terms of weddings is house weddings, where future spouses book a single Western-style detached house in which the wedding ceremony and reception take place. In the neighborhood of Rainbow Bridge in Nagoya, there is even a “wedding village” that boasts not only a church, but also an Italian house, a French house, and an English one. The name “wedding village” is in itself something extraordinary.

In his 1993 film The Nightmare Before Christmas, Tim Burton shows a “Christmas Town” and a “Halloween Town” where seasonal celebrations last all year round; but this takes place in a fairy tale whereas the “wedding villages” of Japan are completely real.

Finally, I would like to mention a science fiction novel with a sociological inclination: Ogawa Issui’s The Next Continent (Dai roku tairiku, Hayakawa bunko, 2003). In it, an entrepreneur contemplates setting up a permanent base on the south pole of the Moon and simulates what could be done with his limited financial and technical means. After giving it a lot of thought, he decides to establish on the moon not a base but a place to celebrate weddings. The entrepreneur reasons that “People will be ready to make the trip to celebrate their wedding, even if the price is high. Wherever one goes in this world, there are always parents who wish to mark the beginnings in the life of their sons and daughters. We must consider a minimum of two couples per trip at a per-couple price of 200 million yen (about 1.333 million euros). There will be certainly candidates for a stay of two nights and three days, with a wedding ceremony and a honeymoon included in the package; in other words a real ‘honey Moon,’ for 400 million yen”. And eventually the main protagonist of Ogawa Issui’s science-fiction novel builds a church on the moon to celebrate cosmic weddings.

Originally translated from Japanese by Marie Maurin

Article published in Stream 01 in 2008.